The funny thing about purity is that it can often lead to sterility. Mix things up a bit and all sorts of unique and unforeseen combinations can result.

Of course the act of 'mixing things up' can also be difficult or worse. People don't always like the challenge of the new. Stasis can be very comforting.

So it was for Joe Harriott. His music was a constant example of trying to 'mix things up'. Although his Free Form experiments were daring and original, his playing was not inherently Jamaican, or British for that matter. His musical building blocks were from the US and he used these to build roads in new and unforeseen directions which would ultimately separate his music from that of his hero Charlie Parker (here).

Musics from outside Europe, often from countries in the British Empire, or recently freed from it, had been increasingly common in Britain since the Second World War. Kwela (read about it here), calypso, ska, highlife, Latin American music as well as many others had been gradually making inroads into the consciousnesses of the British record buying public.

Not only that but the people who made that music had also been coming to Britain. People like Joe Harriott and John Mayer.

Pat Matshikiza, who wrote the South African jazz opera, King Kong (here), in his short and very moving autobiography recounts coming to London and being thrown together with others from across Africa and the West Indies, their differences momentarily put aside by their shared experiences under colonial rule as well as the inability of Londoners to think of any black person as anything but 'African'.

In many ways Harriott and Mayer's Indo-Jazz Double Quartet was a product of the collapse of the British Empire. How else to explain the 'rainbow nation' of musicians? Lead by an Indian and a Jamaican, including musicians from both countries, as well as from elsewhere in the West Indies, England and Scotland, the band was multi-racial and multi-national. But before we get carried away, here is John Mayer on the hostility that the band sometimes received: "Joe Harriott was a man who took all the stick, like myself. We took all the stick from everybody because I was Indian and he was a Jamaican." You only need to read Val Wilmer's marvellous book My Mother Told Me There Would Be Days Like These, to appreciate that most people in Britain had little understanding of cultures outside of their own, much less of people outside of their own country. Wilmer also wonderfully evokes the London of African exiles and immigrants trying to assert their independence and that of their homelands.

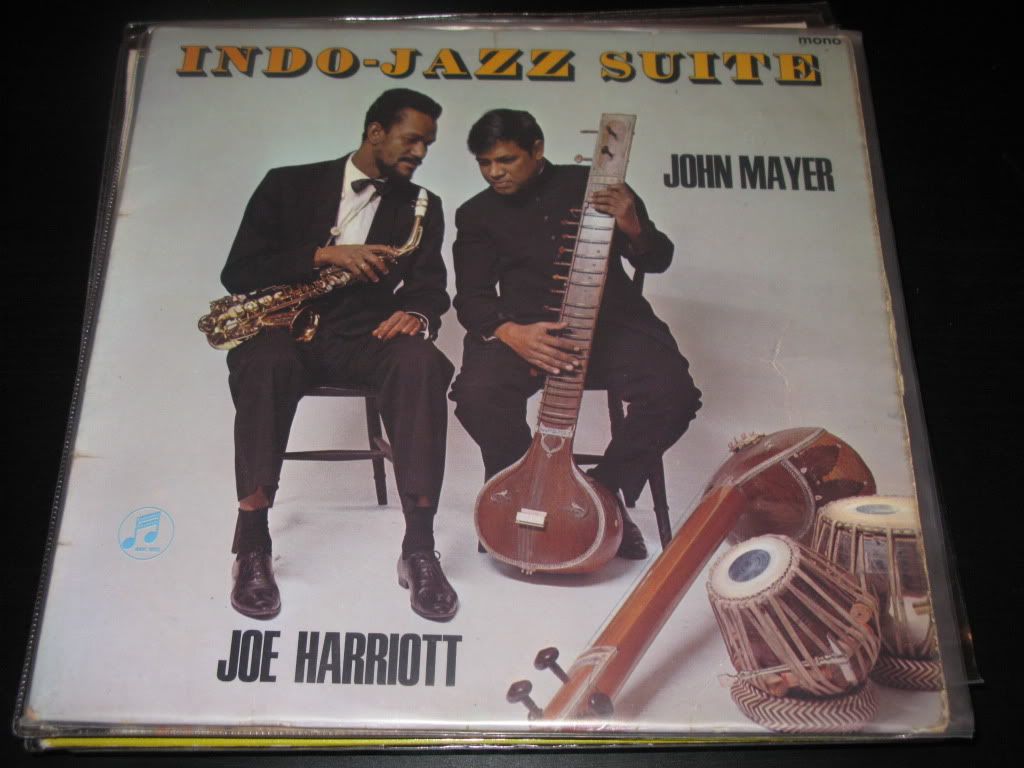

John Mayer was a classically trained violinist and composer from Calcutta. He had come to London to play in the London Philharmonic but his ambitions as a composer made this difficult for him. A chance meeting with producer Denis Preston lead to him composing a jazz piece (which he hurriedly wrote from scratch the night before the recording) and this in turn led to the concept of the double quintet. There is some dispute as to who originally had the idea, but I don't think that matters.

In my opinion Denis Preston was Britain's answer to Bob Thiele. In America he would have been running a label like Impulse. As it was, his Lansdowne Records and the Lansdowne Recordings he produced for EMI, embraced the best of British jazz but were also wildly experimental and adventurous. Preston made jazz records with Indian musicians, Ghanaian drummers (here) and (here), Goan guitarists, some Jamaican avant-garde free-form, classically inspired serial compositions, jazz and poetry, jazz inspired by poetry, he even produced Stan Tracey's tribute to Duke Ellington and, if he had been in America like Bob Thiele, he would have got Duke himself to play. Not all the musicians he worked with appreciated his style, indeed many allege he ripped them off, but like Thiele, he got the best from them and those who did fall for him remained loyal for life.

The Indo-Jazz Suite is not the first jazz record which used sitar. This accolade must go to a Bud Shank record in 1961 which used Ravi Shankar for one track. What is completely different about the Indo-Jazz Suite, what elevates it, and all of the Harriott/Mayer collaborations, above mere exotica, is that it is not music that utilises Indian instruments for the sake of their 'foreigness'. Rather it is an amalgam of an Indian compositional tradition and a jazz tradition. For me, why they are superior to Bill Plummer's Cosmic Brotherhood and Emil Richards' Microtonal Blues Band (read about them here and here), is that Mayer was the driving force and not Harriott. In a way, this could only have happened in London. In America in the fifties and sixties, non-Americans, whether from Indian, Africa or South America, were only exotic sidemen. Perversely, the hangover from Empire, acknowledged in the sleeve notes to the Indo Jazz Suite by reference to Rudyard Kipling, the arch-defender of colonialism and the Empire, allowed Mayer, and to a lesser extent Harriott, to be given control of the music.

All the tracks on all three Harriott/Mayer Indo-Jazz records were composed by Mayer - although one track is an adaptation of Harriott's Subjecty and one a co-composition with Pat Smythe. This really does mean that it is Indian music plus jazz and not jazz with some Indian sounds to spice it up - although this was an accusation levelled at the music at the time. It is Indo Jazz and not Jazz plus Indian music.

Nevertheless, without Harriott, I don't believe the music would have the force that it does. He is completely uncompromising. His playing is not above the Indian ragas, or even weaving between the pulse of the Indian players. He is harsh, abrasive, cutting this way and that through the music, carving out his own space that is completely Joe Harriott. Perhaps it shouldn't work but it does. He brings the hard edge of his free form playing and forces it to mix with Mayer's structures. It is quite brilliant.

Another factor in the music is that Harriott and Pat Smythe are the only constants in the jazz side of the double quintet. The Indian classical side (really a quartet plus classically trained flutist Chris Taylor) remain unchanged through all three records. I think that this provides a base for the Indian side of the music to remain dominant while the jazz side of the equation is constantly learning how to fit in.

Coleridge Goode, who played on both Indo Jazz Fusion records but not the Indo Jazz Suite recounts in his autobiography how complex the process of producing the music was. His take on it was that the jazz musicians would have to practise to be able to play in the different time signatures and different modes so that the Indian musicians could join them.

I can hear a definite development from the first record through to, in my view without doubt the best of the three, the last record. In the Indo-Jazz Suite there is a tentative feel to the playing and the music as though no one is quite sure where it will go and how to play. Harriott sounds crisp and sharp but he is not as completely in control as he would become.

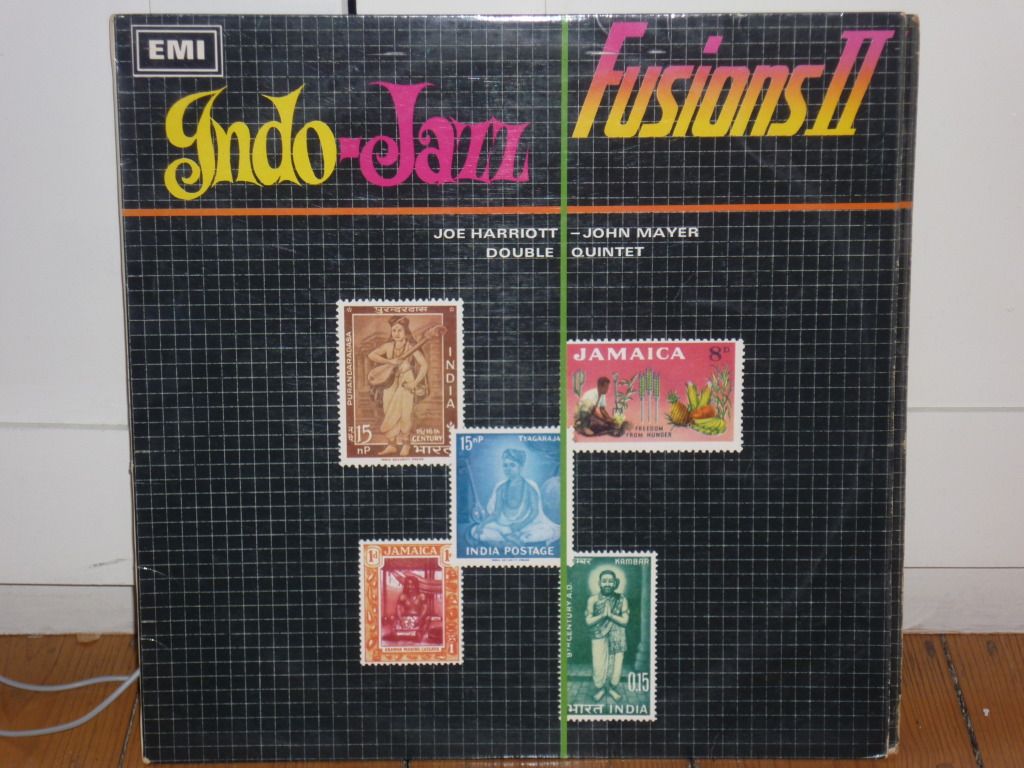

I guess, given the success of the Indo Jazz Suite, and the touring that followed it should not be a surprise that the band improved. For Indo-Jazz Fusions, Harriott is joined by Coleridge Goode (who replaced Eddie Blair who would go on to play with the Mahavishnu Orchestra with that other lover of Indian music John McLaughlin) and Shake Keane (read about Keane here). Goode found the experience interesting and exhilarating and his autobiography contains a quote from Harriott saying the same thing. However, you have to wonder whether there could ever be room for two leaders and I suspect that having been the leader and song writer for his own quintet it was difficult for Harriott to be a member of the double quintet.

Nevertheless, Indo-Jazz Fusions II is the masterpiece of the three records. Harriott is clearly now at home in the idiom, although ironically he seems to play less. Of the jazz musicians, Smythe and Taylor seem most at home, both of them putting in amazing performances. Meanwhile Diwan Motihar, the sitar player is simply incredible. As Ian Carr says in the sleeve notes "now problems and compromises are over: the fusion has taken place".

All of which makes it a shame that it is Harriott's last Indo-Jazz record.

Mayer would continue with the concept, producing a further album, Etudes. Don't what ever you do make the same mistake that I made. I saw the above record from France, which on the reverse is credited as including Harriott. It doesn't. It is Mayer's Etudes repackaged to fool idiots like me. Sax duties are taken up by Tony Coe, with Kenny Wheeler on trumpet and Goode still on bass. The Indian musicians are still the same as the other Indo-Jazz records.

It is a good record, although Harriott's presence is sorely missed. Coe, as good as he is, simply doesn't have the irascible character to take on the Indian aspect of the music with the result that he is too understanding and understated. Good but not great.

Clearly other people noticed the success of Indo-Jazz. The project was lucky in its timing with George Harrison's adoption of the sitar and a general turning towards Eastern mysticism amongst hippies. A number of sitarsploitation records would be released on both sides of the Atlantic to cash-in on this growing desire for non-Western sounds. In many ways this was simply an extension of the exotica craze that had taken off in the 1950s. Non-European instruments were pressed into service either covering the hits of today or to give a slightly 'foreign' sound to otherwise western musical forms. Indo-Jazz was different from that but nevertheless benefited from it.

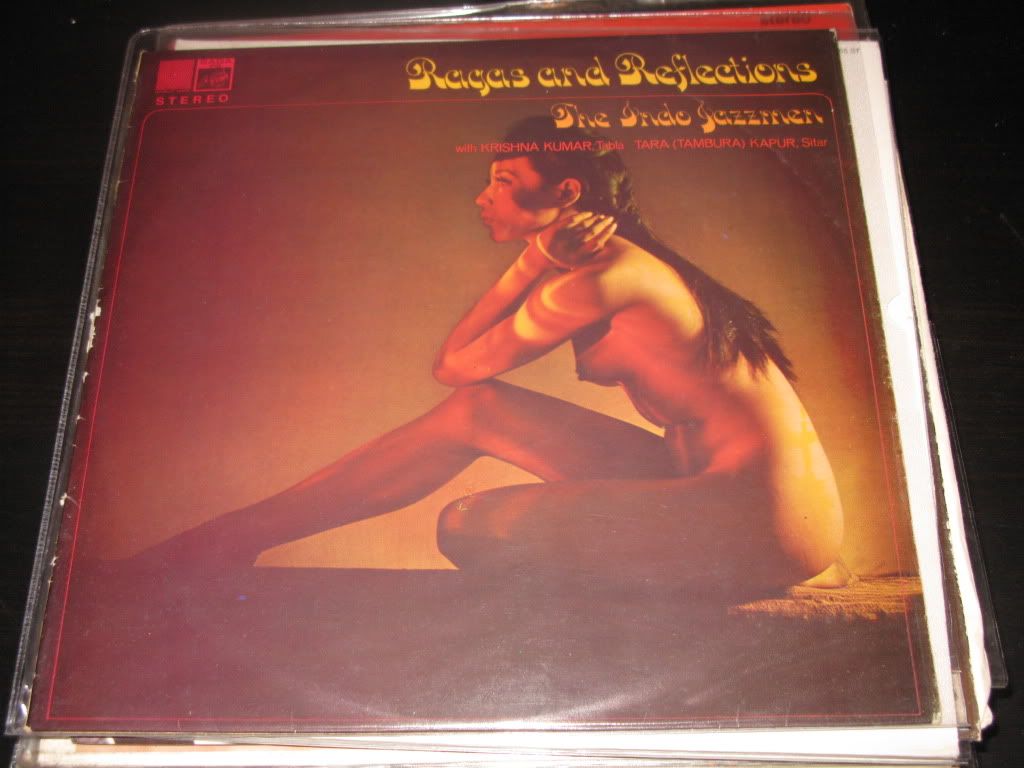

First of the Indo-Jazz cash-ins was Raga's and Reflections by the Indo Jazzmen. The sleeve credits Krishna Kumar on tabla and Tambura Kapur on sitar but does not mention the jazz musicians. The tracks are credited to Issacs who may be Ike Issacs. Anyway, its great stuff and even the inclusion of a Christmas Carol can't pull it down. While the Harriott/Mayer records are cerebral and inquisitive, Ragas and Reflections has more of a feel of a jam session - as befits a cash-in record. I'd like to think that this is some of the same musicians as from the double quintet, moonlighting to make some extra money. However, having listened to this back to back with the Indo-Jazz records, it just doesn't seem likely.

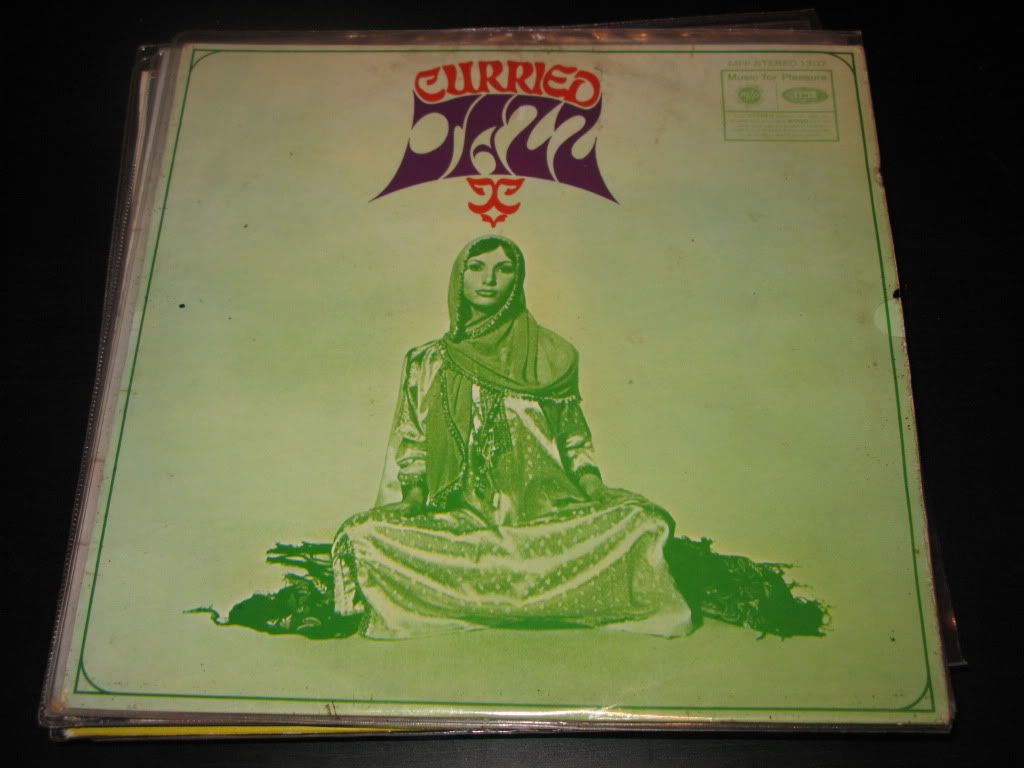

Finally, the last hurrah for Indo-Jazz, we get Curried Jazz by the Indo British Ensemble. The band includes Kenny Wheeler who had played with John Mayer as well as the Australian Chris Karan on tabla which I feel just adds to the Empire feel of the thing. The opening track Yaman (The Colonel's Lady) is one of my favourites. However, despite the inclusion of Dev Kumar on sitar and Sitara on tabla the whole thing is arranged and composed by a Brit Victor Graham. Jazz with an Indian flavour indeed.

Indian music would continue to influence jazz, and jazz musicians would continue to be interested in musics from around the world and use 'exotic' instruments to produce usual sounds. However, the collaboration between Harriott and Mayer would prove to be the high point of this hybrid music.

No comments:

Post a Comment