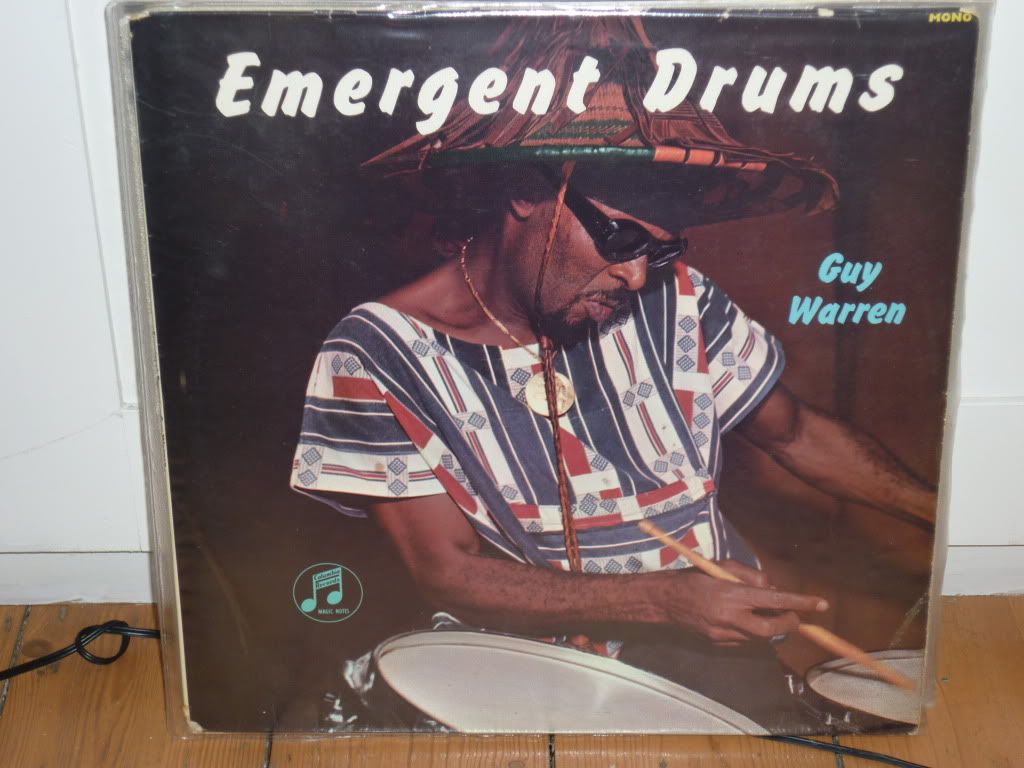

As you may know I am a huge Guy Warren fan.

I don't think, however, in this instance I can say anything that is going to improve on the great man's own sleeve notes for his own record.

I guess I want only to point out his love of his country and continent, particulary at a time of serious political problems, his love of jazz and his interest in using the studio as a tool to develop his music. A man very much ahead of his time

Click here for the music

Hail! The Osagyefo is a rhythm portrait of President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. I borrowed the stirring Atumpan (Ashanti) rhythms of Ghana and used two jazz drums to execute my painting here. I cut this performance at one isttnig and there was no dubbing.

A Recital for Flute and Drums. I had to use the techniques of dubbing for this one. I first played the African bamboo flute, accompanying myself at the same tie with the rhythm of ankle bells tied to my right foot. Next I dubbed in the drum part - and the result is just what I wanted: a loose, swinging rhythm, suporting a swinging loose melody. Are you with it?

I recorde the bell part of An Akwapim Theme first and dubbed the drums on this afterwards. (That clear, tinkling sound, by the way, is the result of my forgetting to bring along a bell to the studio. There were two empty strong glass ashtrays lying around - and one of them came in pretty handy! Which gives me the opportunit to emphasis that, in most African music, it's not so much what yu use to get the desired effect, but how well you can play your part with what you have, and above all, if the sound it right!) The rhythm here is built to urge and move forward... this is the kind of rhythm that was used by the Akwapims of old Ghana, in their wars with the Ashantis. Even now, when it is played, you can feel the same sense of urgency all around...

The Blind Boy again uses the dubbing technique. I first played the African flute, laid it aside and, as this was played back, recorded the jazz drums on top of it as an extension of the theme,returning to the flute for a third track and out. I dubbed the 'talking drum' passage also as an extension of the theme. The title was suggested by a blind youth who wanders around the city of Accra, the capital of Ghana, playing his flute and accompanied by another boy who performs on a single African shaker. This second boy is also the eyes of the team: he plays an accompaniment, dances, collects the pennies, and guides his companion through town.

Black Flute. When I take my bamboo flute, walk down that little meandering, laterite road somwhere in teh county, and take in nature ... then I blow my blues - the blues that comes from nowhere and goes nowhere because it is part of us. It's happy and it's sad. It's life and it's death. That's the blues!

In Buddhism, Prajana means self-nature, the realisation of the SELF. In the studio, I sat behind my two sets of drums and allowed my self to emerge. That's all I can say about Prajana. (I recorded the jazz drums and voice first, and then dubbed in the conga. Towards the end, the jazz drums had introduced a few break patterns. When I took up the conga, it started to solo in and out and in between. The jazz drums at this point sound as if they are almost twisting around the conga - but in a split second they break away and start to do a ritardo - kind of sliding to a stop. Such was the feel that existed during the dubbing that I shaded the conga solo right there into the jazz drums and the two sets of percussion slid out together in perfect concord.)

Babinga Babenzele! There was no dubbing in this pygmy drum suite from the Congo: it was recorded straight and at one take. I sat behind two sets of jazz drums and distributed rhythms to each drum in the twin ensemble, handling at the same time a bamboo flute for opening and fade away.

The Babingas are a pygmy tribe in the Congo. They are subdivided into the Bangombes and the Banenzeles, though both groups are essentially the same. For their music, the Babingas either yodel or play single-note flutes each of which has been pitched differently. And there are drums, too. For many years it was believed that only nativesof the Tyrol or other dwellers of mountainous areas yodelled. The Babingas - who live in the middle Congo, where there are no mountains - give the lie to this.

This suite is supposed to give you an idea of the music of the Babingas. A team of flautists come together to play on their single-note instruments: they perform in such smooth succession, one after the other, that they produce a hightly rhythmic melodic line. At the same time, the drummers man the drums. Teh village swings. As we approach, the music gets louder, more intense. Now we join in the fun and dance until we are exhausted, knocked out. Finally, we free ourselves from this musical hypnotism and depart. As we get out of range, the flutes fade - but we can still hear the two master drums. They are powerful, this pair - they were the ones we heard first! Now, at last, we still hear them in the distance ... like the alpha and omega of the jungle.

The Agasiga rhthym comes from Central Africa, from Watutsi-land. Like all Watutsi rythyms, it is slow, majestic. I cut the piano part first and dubbed the rythym and voice on top.

The music you here now paints you a picture of what is happening in Africa today, not forgetting what happened yesterday. Many live have been lost. Many homes have been broken. But out of chaos will yet rise the power of the new Africa.

I don't think, however, in this instance I can say anything that is going to improve on the great man's own sleeve notes for his own record.

I guess I want only to point out his love of his country and continent, particulary at a time of serious political problems, his love of jazz and his interest in using the studio as a tool to develop his music. A man very much ahead of his time

Click here for the music

Hail! The Osagyefo is a rhythm portrait of President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. I borrowed the stirring Atumpan (Ashanti) rhythms of Ghana and used two jazz drums to execute my painting here. I cut this performance at one isttnig and there was no dubbing.

A Recital for Flute and Drums. I had to use the techniques of dubbing for this one. I first played the African bamboo flute, accompanying myself at the same tie with the rhythm of ankle bells tied to my right foot. Next I dubbed in the drum part - and the result is just what I wanted: a loose, swinging rhythm, suporting a swinging loose melody. Are you with it?

I recorde the bell part of An Akwapim Theme first and dubbed the drums on this afterwards. (That clear, tinkling sound, by the way, is the result of my forgetting to bring along a bell to the studio. There were two empty strong glass ashtrays lying around - and one of them came in pretty handy! Which gives me the opportunit to emphasis that, in most African music, it's not so much what yu use to get the desired effect, but how well you can play your part with what you have, and above all, if the sound it right!) The rhythm here is built to urge and move forward... this is the kind of rhythm that was used by the Akwapims of old Ghana, in their wars with the Ashantis. Even now, when it is played, you can feel the same sense of urgency all around...

The Blind Boy again uses the dubbing technique. I first played the African flute, laid it aside and, as this was played back, recorded the jazz drums on top of it as an extension of the theme,returning to the flute for a third track and out. I dubbed the 'talking drum' passage also as an extension of the theme. The title was suggested by a blind youth who wanders around the city of Accra, the capital of Ghana, playing his flute and accompanied by another boy who performs on a single African shaker. This second boy is also the eyes of the team: he plays an accompaniment, dances, collects the pennies, and guides his companion through town.

Black Flute. When I take my bamboo flute, walk down that little meandering, laterite road somwhere in teh county, and take in nature ... then I blow my blues - the blues that comes from nowhere and goes nowhere because it is part of us. It's happy and it's sad. It's life and it's death. That's the blues!

In Buddhism, Prajana means self-nature, the realisation of the SELF. In the studio, I sat behind my two sets of drums and allowed my self to emerge. That's all I can say about Prajana. (I recorded the jazz drums and voice first, and then dubbed in the conga. Towards the end, the jazz drums had introduced a few break patterns. When I took up the conga, it started to solo in and out and in between. The jazz drums at this point sound as if they are almost twisting around the conga - but in a split second they break away and start to do a ritardo - kind of sliding to a stop. Such was the feel that existed during the dubbing that I shaded the conga solo right there into the jazz drums and the two sets of percussion slid out together in perfect concord.)

Babinga Babenzele! There was no dubbing in this pygmy drum suite from the Congo: it was recorded straight and at one take. I sat behind two sets of jazz drums and distributed rhythms to each drum in the twin ensemble, handling at the same time a bamboo flute for opening and fade away.

The Babingas are a pygmy tribe in the Congo. They are subdivided into the Bangombes and the Banenzeles, though both groups are essentially the same. For their music, the Babingas either yodel or play single-note flutes each of which has been pitched differently. And there are drums, too. For many years it was believed that only nativesof the Tyrol or other dwellers of mountainous areas yodelled. The Babingas - who live in the middle Congo, where there are no mountains - give the lie to this.

This suite is supposed to give you an idea of the music of the Babingas. A team of flautists come together to play on their single-note instruments: they perform in such smooth succession, one after the other, that they produce a hightly rhythmic melodic line. At the same time, the drummers man the drums. Teh village swings. As we approach, the music gets louder, more intense. Now we join in the fun and dance until we are exhausted, knocked out. Finally, we free ourselves from this musical hypnotism and depart. As we get out of range, the flutes fade - but we can still hear the two master drums. They are powerful, this pair - they were the ones we heard first! Now, at last, we still hear them in the distance ... like the alpha and omega of the jungle.

The Agasiga rhthym comes from Central Africa, from Watutsi-land. Like all Watutsi rythyms, it is slow, majestic. I cut the piano part first and dubbed the rythym and voice on top.

The music you here now paints you a picture of what is happening in Africa today, not forgetting what happened yesterday. Many live have been lost. Many homes have been broken. But out of chaos will yet rise the power of the new Africa.

Great Post, I'd love to hear this! Any chance? Thanks :-)

ReplyDelete