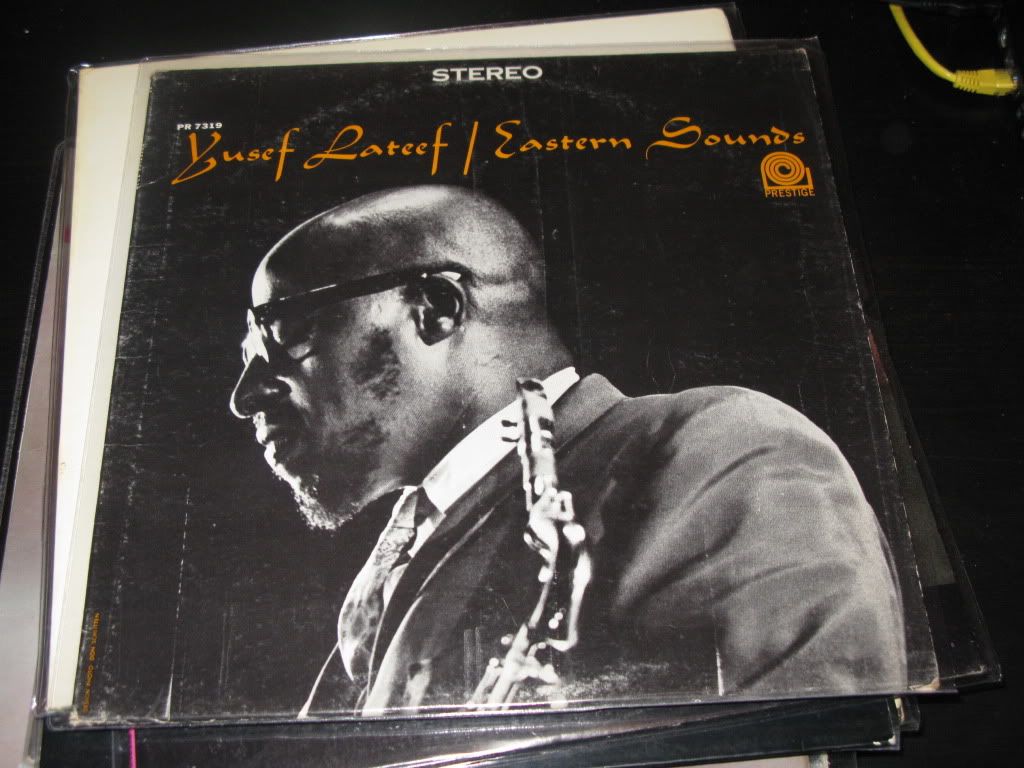

I'm not sure I can do justice to this record. Whatever I write will only scratch the surface of what this amazing record has to offer. I feel as though I have decided to write about A Love Supreme or Milestones!

For me, it is a cornerstone of my love of jazz. It opened my ears to the potential that the music has and the fascination that I have for the exploratory nature of jazz stems directly from Eastern Sounds. Like all great jazz records it not only shows its jazz antecedents, it adds original elements, and the resulting mix points the way towards a new approach to the music.

It may sound slightly improbably but I found this record in a charity shop.I was out to lunch with my wife and had dropped her off at the restaurant while I parked the car. As I walked back to the restaurant I went passed a charity shop. Someone had obviously just dropped off a jazz collection, or perhaps it had been there for some time and the 'real' gems had already been bought. To find any jazz records in charity shops is pretty rare. Over many years I've been lucky enough to find a handful, but the reality is that you are more likely to find records by military dance bands or soundtracks to the Sound of Music than anything jazzy -much less original US pressings in perfect condition! Needless to say when I finally met up with my wife, a large bag of records under my arm, she was not very pleased that I had taken time off from being a husband to be a record collector instead!

But it was all worth it for Eastern Sounds.

This album was recorded in 1961. Lateef had been recording steadily for the previous five years, producing as many as four albums a year in 1957 and in each recording he included at least one experimental track. Often the experiment was the use of an unusual (for jazz) instrument such as an oboe, a piccolo or something from another country.

Lateef's interest in the music of Africa, initially the music of North Africa, stemmed from his conversion to Islam in the early 1950s. As he puts it in his autobiography, when faced with the prospect of having to produce records each year he realised that he would need something more than, then current, hard bop. "To break the mould, I began to study other instruments from different cultures. This new pursuit meant I had to spend time in the public library doing research on Africa, India, Japan and China."

Prior to Eastern Sounds, Lateef has been involved in Olatunji's Zungo and Randy Weston's Uhuru albums. Both records took their inspiration from Africa, the second particularly celebrating the recent withdrawal of British colonialism from many African countries. Music from Africa, particularly Nigeria in Olatunji's case, was used for both records and although Lateef's playing is not decisive on either recording, I think it is an indication of the man's interest in music from outside of America as well as his technical ability to play in other idioms.

Intriguingly, however, the recording Lateef produced of his own music prior to Eastern Sounds is Lost In Sound, which to my ears sounds very much a straight forward, of its time, hard bop record. While the record that followed Eastern Sounds, was Into Something, which again is less experimental than Eastern Sounds. What makes this record stand out from the records Lateef was making at the time, and in some ways from all the records he would ever make, is its relentless experimental approach. With the exception of Don't Blame Me, each track has something different, not just unusual instruments, but also unusual approaches to jazz, ,choices of tracks and influences. Ironically, although it is the least experimental track on the record, the writer of the linear notes, Joe Goldberg pays it more attention than any of the tracks. Perhaps he felt most at home with it?

Lateef's band comprised Barry Harris on piano, Ernie Farrow on bass and Lex Humphries on drums. They are all very competent musicians in the hard bop style and Harris is particularly good throughout, both inventive and sympathetic to Lateef and playing some really fine solos. However, I don't think it is disparaging to these musicians to say that I doubt they could have produced such a classic record without their leader.

The record kicks off with The Plum Blossom on which Lateef plays a Chinese globular flute. It produces such a particular sound that I have never heard anything like it on a jazz record. With some fine piano work from Harris and some interesting bass work from Farrow (is it the rabat he is playing? What kind of instrument is it?) the minimal nature of the song, its repetitive nature, its paucity of percussion and overall simplicity make it utterly captivating.

Blues for the Orient is slightly more conventional except that Lateef is playing the oboe rather than his tenor. This gives the track the, no doubted intended, 'oriental' feel. Its clearly an attempt to merge the American blues idiom with music from the 'orient' as the title tell us. To my ears there is a lot of blues and not a lot of orient - unless the oboe is all the orient there is!

Chinq Miau is, according to the sleeve notes, so-called because of a scale in Chinese music. Based on nothing more than a hunch I wonder if it is the most 'authentic' track on the record! While still 'jazz' it also points the way to the potential for something else, something more.

Lateef's interest in exotica is also evident in the two movie themes on the record. Lateef's versions of the Love Theme from Spartacus, written by Alex North for the movie of the same name, is one of my favourite songs in any genre of all time. Harris's playing is beautiful and Lateef's oboe is keening and heartfelt. I have to admit that there is something almost too deliberately 'exotic' about it, too knowingly 'out-there' and 'strange', as though Lateef is stretching to find the right way to express his interest and love of non-American music. Indeed the choice of covering a song 'about' an exotic place rather than listening to music from that place, only seems strange in the modern world. Coltrane, like Lateef, would listen to ethnographic recordings, but that would be some years hence. These records were not always easy to find in the US and the taste for them was not set in 1961. I am sure that there would be much to be gained from closely comparing this record to Coltrane's Africa Brass of the same year.

Snafu is, to my mind, an acronym from the US military which stands for Situation Normal, All Fucked Up. Is this song in some way a comment on the war in Vietnam. In 1961 the war had yet to become to take quite the divisive position in the US that it would later take. However, many young soldiers, disproportionately poor and therefore black, were being sent there to fight. The refrain maintains the 'exotic' feel of the rest of the record although the rhythm section play it fairly straight. I could see this as being the 'experimental' track on another Lateef record. Here is comes across as almost 'straight'.

Following the frenetic Snafu, Purple Flower is achingly slow. Lovely piano from Harris and restrained brushing from Humphries underpin Lateefs deep tenor tone. Makes me think of feeling 'heavy' and 'happy' - too deep to do anything but enjoying it nonetheless.

He also covers another sand and sandals tune, the Love Theme from the Robe. A film that has somewhat lapsed into obscurity, it tells the story of a Roman Centurion assigned to crucify Jesus. Supposedly set in Palestine it was shot in LA but retains a somewhat otherworldly character.

The record closes with the Three Faces of Balal which acts as a coda to Plum Blossom. The instrumentation is similar as is the mood. I am not sure what the Three Face of Balal are, but I doubt the explanation given in the sleeve notes. Could it be another biblical reference to go with the two songs from biblical movies? Perhaps, given the composer's faith, it is not Biblical related, however, it may have a North African reference which would fit with the other tracks on the record.

For me, it is a cornerstone of my love of jazz. It opened my ears to the potential that the music has and the fascination that I have for the exploratory nature of jazz stems directly from Eastern Sounds. Like all great jazz records it not only shows its jazz antecedents, it adds original elements, and the resulting mix points the way towards a new approach to the music.

It may sound slightly improbably but I found this record in a charity shop.I was out to lunch with my wife and had dropped her off at the restaurant while I parked the car. As I walked back to the restaurant I went passed a charity shop. Someone had obviously just dropped off a jazz collection, or perhaps it had been there for some time and the 'real' gems had already been bought. To find any jazz records in charity shops is pretty rare. Over many years I've been lucky enough to find a handful, but the reality is that you are more likely to find records by military dance bands or soundtracks to the Sound of Music than anything jazzy -much less original US pressings in perfect condition! Needless to say when I finally met up with my wife, a large bag of records under my arm, she was not very pleased that I had taken time off from being a husband to be a record collector instead!

But it was all worth it for Eastern Sounds.

This album was recorded in 1961. Lateef had been recording steadily for the previous five years, producing as many as four albums a year in 1957 and in each recording he included at least one experimental track. Often the experiment was the use of an unusual (for jazz) instrument such as an oboe, a piccolo or something from another country.

Lateef's interest in the music of Africa, initially the music of North Africa, stemmed from his conversion to Islam in the early 1950s. As he puts it in his autobiography, when faced with the prospect of having to produce records each year he realised that he would need something more than, then current, hard bop. "To break the mould, I began to study other instruments from different cultures. This new pursuit meant I had to spend time in the public library doing research on Africa, India, Japan and China."

Prior to Eastern Sounds, Lateef has been involved in Olatunji's Zungo and Randy Weston's Uhuru albums. Both records took their inspiration from Africa, the second particularly celebrating the recent withdrawal of British colonialism from many African countries. Music from Africa, particularly Nigeria in Olatunji's case, was used for both records and although Lateef's playing is not decisive on either recording, I think it is an indication of the man's interest in music from outside of America as well as his technical ability to play in other idioms.

Intriguingly, however, the recording Lateef produced of his own music prior to Eastern Sounds is Lost In Sound, which to my ears sounds very much a straight forward, of its time, hard bop record. While the record that followed Eastern Sounds, was Into Something, which again is less experimental than Eastern Sounds. What makes this record stand out from the records Lateef was making at the time, and in some ways from all the records he would ever make, is its relentless experimental approach. With the exception of Don't Blame Me, each track has something different, not just unusual instruments, but also unusual approaches to jazz, ,choices of tracks and influences. Ironically, although it is the least experimental track on the record, the writer of the linear notes, Joe Goldberg pays it more attention than any of the tracks. Perhaps he felt most at home with it?

Lateef's band comprised Barry Harris on piano, Ernie Farrow on bass and Lex Humphries on drums. They are all very competent musicians in the hard bop style and Harris is particularly good throughout, both inventive and sympathetic to Lateef and playing some really fine solos. However, I don't think it is disparaging to these musicians to say that I doubt they could have produced such a classic record without their leader.

The record kicks off with The Plum Blossom on which Lateef plays a Chinese globular flute. It produces such a particular sound that I have never heard anything like it on a jazz record. With some fine piano work from Harris and some interesting bass work from Farrow (is it the rabat he is playing? What kind of instrument is it?) the minimal nature of the song, its repetitive nature, its paucity of percussion and overall simplicity make it utterly captivating.

Blues for the Orient is slightly more conventional except that Lateef is playing the oboe rather than his tenor. This gives the track the, no doubted intended, 'oriental' feel. Its clearly an attempt to merge the American blues idiom with music from the 'orient' as the title tell us. To my ears there is a lot of blues and not a lot of orient - unless the oboe is all the orient there is!

Chinq Miau is, according to the sleeve notes, so-called because of a scale in Chinese music. Based on nothing more than a hunch I wonder if it is the most 'authentic' track on the record! While still 'jazz' it also points the way to the potential for something else, something more.

Lateef's interest in exotica is also evident in the two movie themes on the record. Lateef's versions of the Love Theme from Spartacus, written by Alex North for the movie of the same name, is one of my favourite songs in any genre of all time. Harris's playing is beautiful and Lateef's oboe is keening and heartfelt. I have to admit that there is something almost too deliberately 'exotic' about it, too knowingly 'out-there' and 'strange', as though Lateef is stretching to find the right way to express his interest and love of non-American music. Indeed the choice of covering a song 'about' an exotic place rather than listening to music from that place, only seems strange in the modern world. Coltrane, like Lateef, would listen to ethnographic recordings, but that would be some years hence. These records were not always easy to find in the US and the taste for them was not set in 1961. I am sure that there would be much to be gained from closely comparing this record to Coltrane's Africa Brass of the same year.

Snafu is, to my mind, an acronym from the US military which stands for Situation Normal, All Fucked Up. Is this song in some way a comment on the war in Vietnam. In 1961 the war had yet to become to take quite the divisive position in the US that it would later take. However, many young soldiers, disproportionately poor and therefore black, were being sent there to fight. The refrain maintains the 'exotic' feel of the rest of the record although the rhythm section play it fairly straight. I could see this as being the 'experimental' track on another Lateef record. Here is comes across as almost 'straight'.

Following the frenetic Snafu, Purple Flower is achingly slow. Lovely piano from Harris and restrained brushing from Humphries underpin Lateefs deep tenor tone. Makes me think of feeling 'heavy' and 'happy' - too deep to do anything but enjoying it nonetheless.

He also covers another sand and sandals tune, the Love Theme from the Robe. A film that has somewhat lapsed into obscurity, it tells the story of a Roman Centurion assigned to crucify Jesus. Supposedly set in Palestine it was shot in LA but retains a somewhat otherworldly character.

The record closes with the Three Faces of Balal which acts as a coda to Plum Blossom. The instrumentation is similar as is the mood. I am not sure what the Three Face of Balal are, but I doubt the explanation given in the sleeve notes. Could it be another biblical reference to go with the two songs from biblical movies? Perhaps, given the composer's faith, it is not Biblical related, however, it may have a North African reference which would fit with the other tracks on the record.

Hii nice reading your blog

ReplyDelete