That Charlie Parker has a lot to answer for. Not only did he popularise heroin in jazz he also legitimised the mix of jazz and 'strings'. His 1950 record, Charlie Parker With Strings, under the auspices of Norman Granz, was an attempt to give jazz some mainstream acceptance. The session paired Parker, a wild improviser, with a chamber orchestra of three violins, viola, cello, harp, oboe and English horn. They were joined by a jazz rhythm section. The results have been debated ever since. The decision to only record standards, understandable given the nature of the studio 'band', has been criticised. Moreover, it has been claimed that the very nature of Parker's playing and the nature of the classically trained orchestra meant that neither was comfortable nor able to play to their strengths. Finally, the charts by Jimmy Carroll have also been dismissed as being glib and facile. It should, however, be noted that Parker seems to have been very pleased with the results. Not only that, many saw this, and the subsequent 'with strings' sessions, as part of a process of legitimising jazz, of showing a wide public that jazz was not just the music of bordellos and bars (which is precisely why many people liked it!).

Harriott for his part was initially a devotee of Parker and at the start of his career acknowledged it. Indeed the inclusion of Parker's Now's The Time on this record shows that even at this stage of Harriott's career, Bird cast a long shadow.

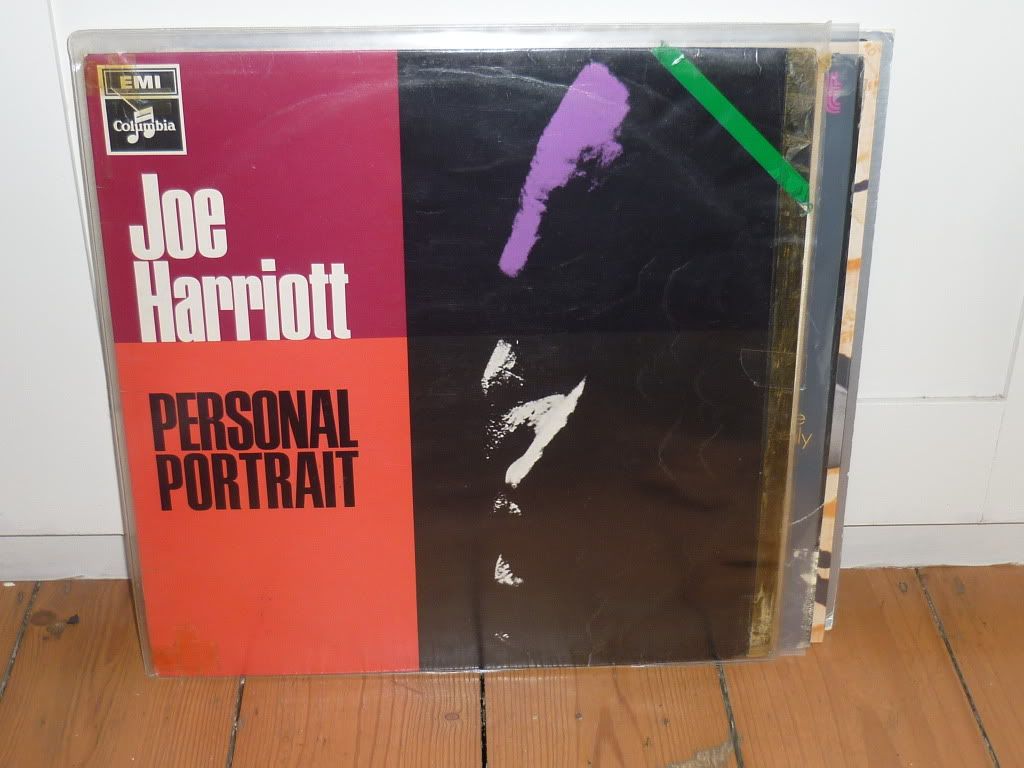

By the time Harriot recorded this record in 1967, which would be his last under his own name, he had not only previously recorded a 'with strings' record, in 1955, but he had also recorded three records with John Mayer. While not pairing him with a string section, the nature of Indian classical music meant that unlike his earlier records with his own Quintet or with Michael Garrick, there was far less space for improvisation and stretching out. Harriott was a veteran of many styles of jazz, many types of band, and many pairing of his music with unusual bedfellows - even poetry!

Denis Preston's effusive linear notes make reference to all of this. He even goes so far as to say that the content of the record is autobiographical and hence presumably the reason for the title. It is, of course, impossible to know if Harriott really did feel that this record reflected his true character. Given the portrait of him painted in Alan Robertson's Fire In His Soul, I doubt that he would ever have done anything as obvious as bare his soul completely.

Nevertheless, it is hard to imagine that the music on this record is a portrait of Harriott. Or if it is, its a portrait of two very different characters. One is the consummate professional, able to play beautifully in any context. The other is the fiery stylist, always probing and stretching what jazz could be - in fact the man behind Free Form.

The string tracks were orchestrated by David Mack. I'm afraid I can't find any information about David Mack, except for the tantalising snippet that he made a record called New Directions in 1964 with, amongst others, Shake Keane and Coleridge Goode. In his autobiography Goode describes it as a very adventurous record let down by the poor quality of the playing. He goes on to describe how constricted he felt by Mack's approach to music and he had no room to improvise - although Keane was expected to improvise over the top. I have never heard or seen this record - if anyone reading this has a copy do please let me know!!!

Goode's description of Mack's approach can, I think, be applied to Personal Portrait. There seems to be a disconnect between the work of the soloist and the rest of the musicians. The orchestra "from across the tracks in the classical world" as Preston says in the sleeve notes are perfectly decent but they are not playing 'with' Harriot. There is an unfortunate harpsichord that, while current in the sixties, adds nothing to the feel of the music. Indeed, at times the orchestration has an almost 'library' or 'filmic' feel to it in that Mack seems to be reaching for some kind of feeling but only reaching cliches and trite phrases.

All is not lost however. As with his college, Shake Keane's solo records, Harriott seems to be have been given a chance to record at least two tracks in which he breaks free. The opening track, Saga opens with some great bongo playing from Monty Babson and restrained drums from Bobby Orr before Harriott plays a jaunty mento. Unfortunately he is soon replaced by a larger horn section. Just as it looks as though the whole track is going to be lost, Stan Tracey leaps in with some characteristically wonderful playing. This seems to enliven Harriott who comes back in, completely in charge of the song and gives a wonderful solo. There's a return of the slightly stiff horn section, some more great bongos and Harriott returns one last time to be joined by bongos and piano and end the track in wonderful style. Perhaps not one of his absolute best but great none the less.

You can listen to it by clicking here

On Abstract Doodle, Harriott is accompanied solely by Scottish pianist and comrade in arms from his Free Form days, Pat Smythe. Where Tracey's playing is strident and forceful, Smythe is lyrical and subtle. He and Harriott create a beautiful duet that shows the depth of understanding the two players had developed through many years of playing. After the other orchestrated tracks, Abstract Doodle burst out of the speakers like a breath of fresh air. What a shame the other tracks aren't comparable. The following track, Mr Blueshead starts like a piece of library music and goes downhill from there. After the inventiveness of Abstract Doodle it is like a splash of cold water.

Enjoy this great piece of music by clicking here

I can't help feel that there is a simliarity in intent and resutl with Shake Keane's solo stuff, particularly That's the Noise, on which Bob Efford, Bobby Orr, Pat Smythe and Stan Tracey also played. You can read about it here

Harriott recorded again after Personal Portrait, most notably with Amancio D'Silva on Hum Domo. As as last solo effort though this record, intended to be Harriott's chance to shine, was not a success. Like his inspiration, Charlie Parker, Harriott would die too young, and having failed to fulfil the great potential that he still had in him.

No comments:

Post a Comment