I seem to be on a bit of roll with drummers at the moment - no pun intended!

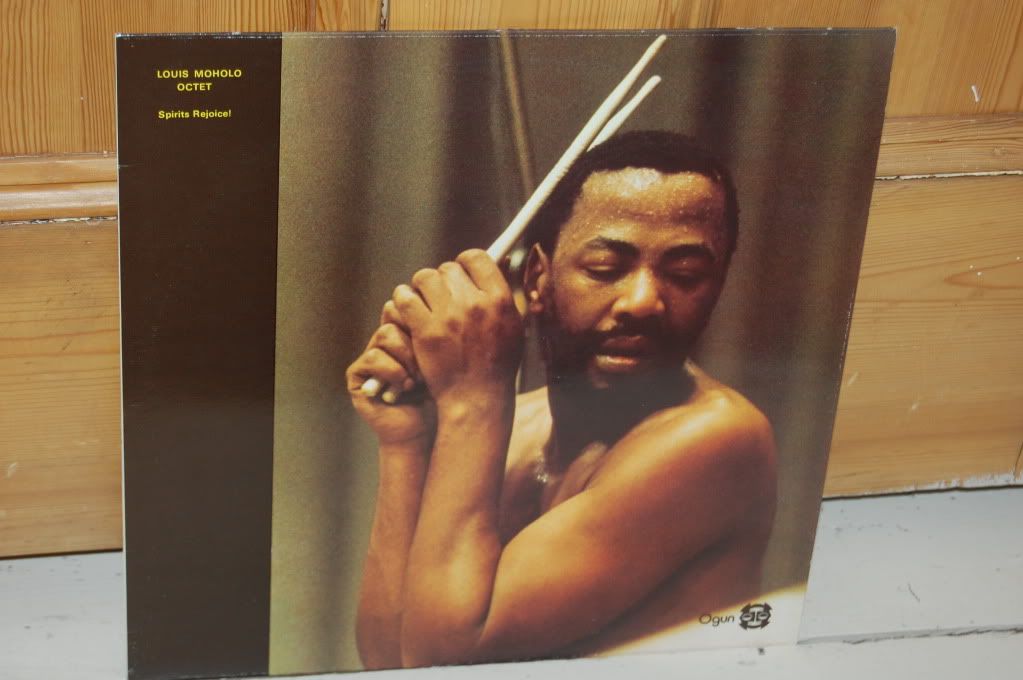

So I've been inspired to pull this record out.

This is the kind of record that my wife hates - too free, too wild, too unconventional.

Louis Moholo is a South African drummer who, together with Chris McGregor, Johnny Dyani, Dudu Pukwana and Mongezi Feza comprised the Blue Notes. Hounded by apharteid they left South Africa in 1968 ostensibly to play at a music festival in the south of France. They never went back.

After France, they made their way to London where they were to have a profound influence on the jazz scene. Their style of playing, their influences and their radical stance encouraged and nurtured other British jazz musicians who were looking for more experimental approaches.

The Blue Notes soon split up as a band but the members continued to play together in many different iterations most famously the Brotherhood of Breath.

In interviews Moholo has said that he enjoyed playing with his countrymen Pukwana, Dyani and Feza above all else. Not only were they wonderful musicians but they shared the bond of being exiles, of being black South Africans in Europe, separated from their families, from their homes and cultures. They would often play with other South African exiles but they knew that they could never go back to an apharteid South Africa. All of the Blue Notes, with the exception of Moholo died young and in exile.

Moholo himself once said: "To leave South Africa and to go to Europe, that was my mistake. I did suffer. I even had a heart attack. And people like Mongezi Feza died from depression. Johnny Dyani also died from a kind of depression. We were not happy overseas, but we were free. We were free. I thank Europe for a lot of things, but for other things, we really missed in Europe: it was very, very hard!"

Political freedom and musical freedom, the two are often equated by Moholo. When one listens to the music the Blue Notes played in South Africa and compares it to the music they created when they came to Europe you can hear that their playing was becoming increasingly freer. Perhaps they felt that they could express themselves in ways that were not possible in South Africa. They were undoubtedly exposed to musicians and recordings that would have been impossible to hear at home.

But I like to think that the rage and anger of being exiles coupled with the sheer joy of being free (musically and politically) came together to make challenging and avante garde music.

If you have trouble with free jazz - then don't listen to this record. However, what lifts it above and beyond most European free jazz in my opinion are the South African elements. I'm no musicologist so I'm not about the go on about marabi, mbaqanga, kwela or other South African styles of music. Suffice it to say that this is music that could only be composed by South Africans.

The Octet comprises Moholo, Evan Parker, Kenny Wheeler, Nick Evans, Radu Malfatti, Keith Tippett, Johnny Dyani and Harry Miller - a mix of Englishmen and South Africans.

For me the highlight is Mongezi Feza's You Ain't Gonna Know Me 'Cos You Think You Know Me. It has a wonderful repeated theme that you will find sticks in the memory and refuses to become dislodged. Kenny Wheeler's trumpet is masterful, but I can't help but wonder what Feza himself would have made of if. By the way is you get the chance, listen to Zim Ngqawana's recent cover of this track.

I also find the last track Wedding Hymn, to be very moving. Composed by Pat Matshikiza for the jazz opera King Kong it is a haunting and beautiful piece of music. King Kong played in London which gave many of the musicians in the orchestra the chance to escape apharteid. Musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masakela, Jonas Gwangwa and the Manhattan Brothers went into voluntary exile. I am sure that Moholo is commenting on his own exile and that of his countrymen by choosing to cover a song from King Kong. By slowing it down he turns a wedding hymn into something that sounds like a funeral march. Surely a comment on the double edged nature of finding your freedom but losing your country. Kenny Wheelers trumpet is again wonderful but Keith Tippett's piano solo is also commanding and Dyani's bass playing is as imaginative and creative as ever.

Throughout the record Moholo's drumming is exemplary - as you would expect. However, this is a recording of a band rather than a soloist and his backing group.

This is the kind of record that my wife hates - too free, too wild, too unconventional.

Louis Moholo is a South African drummer who, together with Chris McGregor, Johnny Dyani, Dudu Pukwana and Mongezi Feza comprised the Blue Notes. Hounded by apharteid they left South Africa in 1968 ostensibly to play at a music festival in the south of France. They never went back.

After France, they made their way to London where they were to have a profound influence on the jazz scene. Their style of playing, their influences and their radical stance encouraged and nurtured other British jazz musicians who were looking for more experimental approaches.

The Blue Notes soon split up as a band but the members continued to play together in many different iterations most famously the Brotherhood of Breath.

In interviews Moholo has said that he enjoyed playing with his countrymen Pukwana, Dyani and Feza above all else. Not only were they wonderful musicians but they shared the bond of being exiles, of being black South Africans in Europe, separated from their families, from their homes and cultures. They would often play with other South African exiles but they knew that they could never go back to an apharteid South Africa. All of the Blue Notes, with the exception of Moholo died young and in exile.

Moholo himself once said: "To leave South Africa and to go to Europe, that was my mistake. I did suffer. I even had a heart attack. And people like Mongezi Feza died from depression. Johnny Dyani also died from a kind of depression. We were not happy overseas, but we were free. We were free. I thank Europe for a lot of things, but for other things, we really missed in Europe: it was very, very hard!"

Political freedom and musical freedom, the two are often equated by Moholo. When one listens to the music the Blue Notes played in South Africa and compares it to the music they created when they came to Europe you can hear that their playing was becoming increasingly freer. Perhaps they felt that they could express themselves in ways that were not possible in South Africa. They were undoubtedly exposed to musicians and recordings that would have been impossible to hear at home.

But I like to think that the rage and anger of being exiles coupled with the sheer joy of being free (musically and politically) came together to make challenging and avante garde music.

If you have trouble with free jazz - then don't listen to this record. However, what lifts it above and beyond most European free jazz in my opinion are the South African elements. I'm no musicologist so I'm not about the go on about marabi, mbaqanga, kwela or other South African styles of music. Suffice it to say that this is music that could only be composed by South Africans.

The Octet comprises Moholo, Evan Parker, Kenny Wheeler, Nick Evans, Radu Malfatti, Keith Tippett, Johnny Dyani and Harry Miller - a mix of Englishmen and South Africans.

For me the highlight is Mongezi Feza's You Ain't Gonna Know Me 'Cos You Think You Know Me. It has a wonderful repeated theme that you will find sticks in the memory and refuses to become dislodged. Kenny Wheeler's trumpet is masterful, but I can't help but wonder what Feza himself would have made of if. By the way is you get the chance, listen to Zim Ngqawana's recent cover of this track.

I also find the last track Wedding Hymn, to be very moving. Composed by Pat Matshikiza for the jazz opera King Kong it is a haunting and beautiful piece of music. King Kong played in London which gave many of the musicians in the orchestra the chance to escape apharteid. Musicians such as Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masakela, Jonas Gwangwa and the Manhattan Brothers went into voluntary exile. I am sure that Moholo is commenting on his own exile and that of his countrymen by choosing to cover a song from King Kong. By slowing it down he turns a wedding hymn into something that sounds like a funeral march. Surely a comment on the double edged nature of finding your freedom but losing your country. Kenny Wheelers trumpet is again wonderful but Keith Tippett's piano solo is also commanding and Dyani's bass playing is as imaginative and creative as ever.

Throughout the record Moholo's drumming is exemplary - as you would expect. However, this is a recording of a band rather than a soloist and his backing group.

No comments:

Post a Comment