Anyway, during one of our trips out there we were having a few drinks at one of my wife's friends and when I mentioned I liked vinyl he ran into the house and came out with a stack of records his mother had given him. I'd like to say that this was one of them but unfortunately it wasn't. However, one of the records was Mannenberg by Dollar Brand and Basil Coatzee. It opened my mind and ears to SA jazz and with the help of the internet I set off in search of other pieces of SA jazz vinyl.

It may come as no surprise that apartheid was as harmful to jazz in South Africa as it was to almost every other form of artistic endeavour. Black South Africans could not move freely so could not go to rehearsals, gigs or recording dates, there were limits to the number of black people who could be together at any one time in case they were engaged in political activity, movement was restricted by the pass system, reasons for being out at night could not include being a musician as the state did not recognise that black people could be musicians, there were few venues in any township where live music could be played and those that did exist were poorly equipet and often violent places, radio stations were Bantu-ised in the same way that much of the rest of black South African life was and therefore jazz struggled to find an outlet and finally bands could not be racially mixed or play to racially mixed audiences and often black performers could not play to white audiences or if they did they had to endure degrading treatment.

In these circumstances its a miracle that any music was produced at all. But people did produce art, poetry, dance and music in the face of great odds.

One of the people who was determined that jazz should have an outlet was Rashid Valley who established the As-Shams, The Sun label in Johannesburg and it is thanks to him, in my opinion, that there is as much jazz on record from the seventies as there is - and there isn't much!

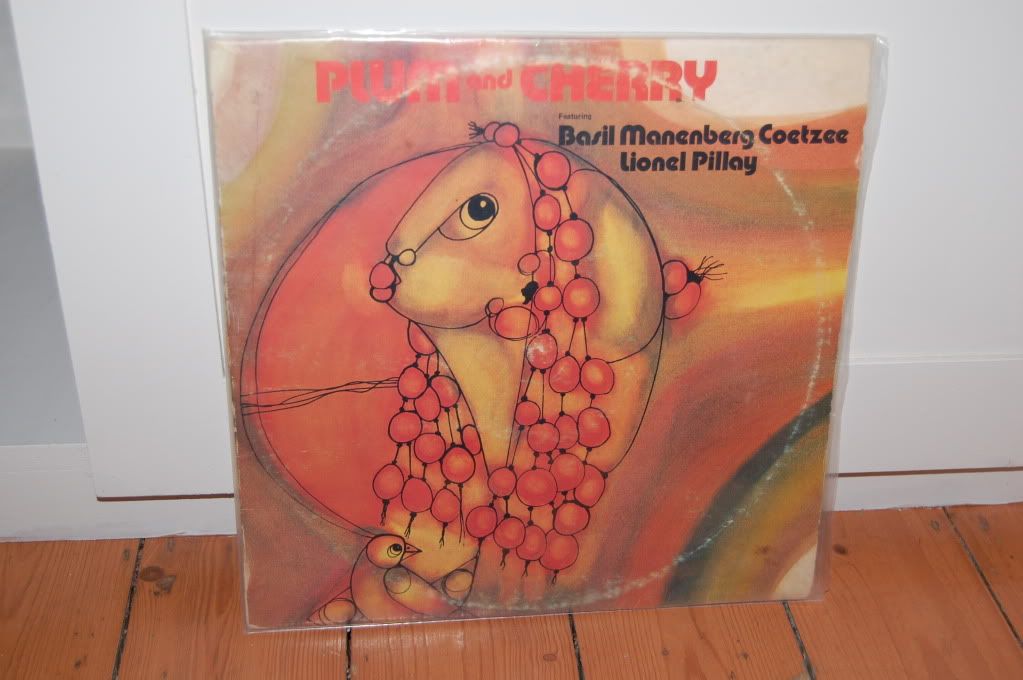

Anyway, enough background what about the music. This record, Plum and Cherry by Lionel Pillay and Basil Coetzee consists of two side-long pieces, Cherry, composed by Dollar Brand and Plum by Lionel Pillay.

In some ways Cherry leaves off from where Mannenbery finished. It's foundation is the repetative, hypnotic and surprisingly slow bass theme by Charles Johnstone that continues almost unchanged for the entire 25 minute and 28 seconds of the track. With restrained soft drumming and percussion from Rod Clark the rhythm section enables Lionel Pillay and Basil Coetzee to explore different tones, imaginative spaces and inflections throughout. This is music to dance to. Indeed my brother in law has danced with my daughter to this track. Within its structure is encorporates elements of an earlier style of South African jazz called marabi but retains some of the sophistication of jazz. Just as with practically every country that produces jazz musicians the issue of American-isms in the music was important in South Africa. I believe in tracks such as this a new particularly South African voice can be heard.

Plum starts with a repeated piano riff that, to my ears, sounds like it was played on the piano used on the Mannenberg track. Has it been treated in some way? I can't say but it makes me think of the pianists lot to arrive at gigs to find an out of tune instrument that he has to make do with.

But rather than repeat the Mannenberg formula, Pillay suddenly introduces an electric organ which takes the tune into an almost disco like area. From the stately rythm of Cherry the listener finds oneself in the middle of a funky, sweating dancefloor. The high hats and congos from Clark would not have been out of place at the Paradise Garage. About half of the way through Pillay brings the piano back into the song and when I first heard it this reminded me of about a thousand house records - but made twenty yearsearlier. If you don't dance to this there is something wrong with you. It may be music for the feet rather than the head but if you let your feet go your head won't mind. By the time the track finishes after nearly nineteen minutes with a refrain of the initial piano riff you're a sweaty happy mess

In some ways this track prefigures what was to happen to the South African music scene. Influences from America and Europe were not just adopted into South African music but incorporated into South African forms to produce new types of music that would shock traditionalists but that would also refuse to be slavish imitations of their sources.

On a final note the wonderful cover painting is by Hargreaves Ntukwana. I would love to know more about him if anyone has any info. And if you have a spare copy of Tete Mbambisa's Didn't You Tell My Mother I'd also love to know.

Here's some music

thank you!

ReplyDelete