If Guy Warren's musical journey was an attempt to introduce African drumming to jazz then one might think that Olatunji succeeded in the attempt. However, rather than fuse jazz and African drums, Olatunji served up a watered down version of traditional Nigerian songs that captivated record buyers and jazz musicians alike.

Babatunde Olatunji was originally from Nigeria, first came to the US to study politics at Morehouse University and only started playing drums when he arrived in the US.

Due to a combination of luck and and good connections Olatunji became known in New York jazz circles as the go-to-guy for African drumming He appears on a number of jazz records of the early 60's appearing on Randy Weston's Uhuru African, Cannonball Adderley's African Waltz, Herbie Mann's Afro-Jazz Sextet and Max Roach's We Insist.

His Drums of Passion LP became a sensation, selling thousands of copies in the US. Unlike Warren and other African drummers such as Solomon Ilori, Olatunji's music was more 'traditional'. Using songs from his homeland and some of his own compositions (most notably Gin-Go Lo-Ba which would go on to become Jingo in the hands of Santana) Drums of Passion came off as a 'genuine' slice of Africa.

It was however, nothing of the sort. Most of the musicians on it were African Americans perhaps most notably drummers and percussionists James 'Chief' Bey (who played with Guy Warren on Themes For African Drums - read about it here), Thomas Taiwo Duvall and Montego Joe (read about his solo records here) and the singers were also from America.

Olatunji was not formerly trained as a drummer and his three co-drummers, by some accounts, provided most of the music and helped him overcome his initial limitations. Indeed in the introduction to his autobiography it is even admitted. However, Olatunji not only got top billing, the help he received remained virtually unknown.

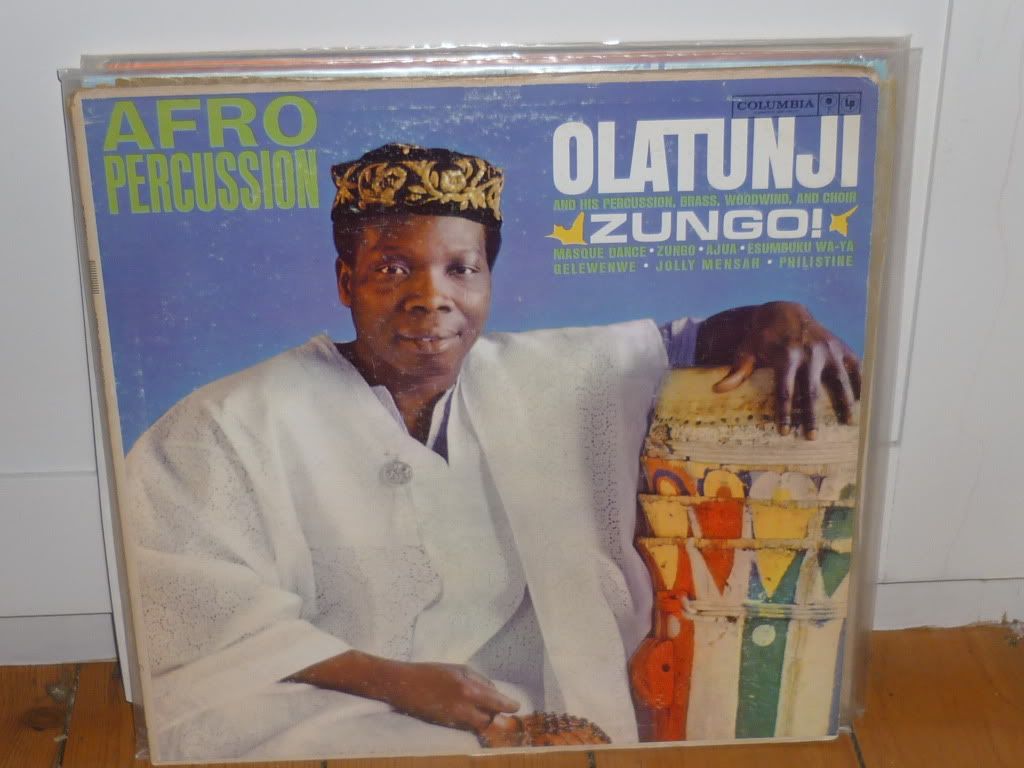

All three percussionists appear on Zungo which was released in 1961, together with Yusef Lateef on winds, Clark Terry on trumpet, George Duvivier on bass, and Ray Barretto on conga and timbalis. Interestingly Lateef, Montego Joe and Chief Bey would go on to play on Blakey's African Beat (read about it here) in 1962, while the previous year, 1960, saw Lateef, Duvivier and Olatunji play on Randy Weston's Uhuru Africa. The 'Africa' link surely doesn't need to be pointed out!

Why was he so popular both with the jazz world and with record buyers if his playing was questionable and his music lacking in authenticity? Part of the answer lies in Lateef's recollections of playing with him. In his autobiography Lateef writes: "Later in 1960, I moved from Mingus to a group led by Babatunde Olatunji, the Nigerian percussionist. Playing with Babatunde was an interesting experience, mostly because for the first time I had to perform without a pianist or bassist in the group. It provided me with a lot of harmonic space and freedom. Olatunji's music also provided a wider appreciation for world music. To this extent he was a pioneer of what is termed today 'world music'."

For Lateef, Olatunji represented an opportunity to play with an authentic African drummer and to learn about African drumming so as to incorporate it into jazz. The same was true of John Coltrane, who became friends with Olatunji and he and Lateef agreed to help him financially with his Center of African Culture. Indeed the last concert that Coltrane played, and the last recording of him playing, was at a benefit for Olatunji's Center. Coltrane was always interested in rhythm and drummers and his love of playing with Elvin Jones because of his fierce drumming style is well documented. Coltrane also said in interviews that he intended to record with Olatunji or at least learn about 'African' drumming and music from him.

Even Nina Simone recorded Zungo, from this album, on her At the Village Gate LP. And Jack Kerouac, according to the sleeve note, loved Olatunji. Guy Warren must have been very put out by the song Jolly Mensah. After all he had actually played with the highlife king!

So, Olatunji represented a potential new musical direction but also a physcial manifestation of pride in Africa and, for African American, African culture. At a time when Africa was coming out of the oppressive period of empire and was yet to succumb to other forms of economic colonialism, the continent could become a source of pride for African Americans. Meanwhile, 1960 also saw the sit in protests in the US (shown in graphic form on the cover of Max Roach's We Insist), while 1961 and 1962 saw more sit ins, freedom rides and boycotts across the Southern states of the US.

However, despite his success both commercially and professionally I find Olatunji's music to be rather flat. It often lacks the rhythmic intricacies of other percussion records, notably by Guy Warren and Solomon Ilori. Both these musicians also strove, and sometime wonderfully succeeded to fuse Western jazz and African 'traditional' music, as well as the already existing fusion that was highlife. Lateef and Coltrane may have been fascinated by Olatunji's music, and I suspect that this was because he was perceived as authentic. They wanted something that sounded 'African' rather than sounding too 'Western'. Through wanting to create a fusion of their music with 'authentic African' music, ironically, American jazz musicians and record buyers ignored the music that already existed that was already a fusion of the two - highlife.

Babatunde Olatunji was originally from Nigeria, first came to the US to study politics at Morehouse University and only started playing drums when he arrived in the US.

Due to a combination of luck and and good connections Olatunji became known in New York jazz circles as the go-to-guy for African drumming He appears on a number of jazz records of the early 60's appearing on Randy Weston's Uhuru African, Cannonball Adderley's African Waltz, Herbie Mann's Afro-Jazz Sextet and Max Roach's We Insist.

His Drums of Passion LP became a sensation, selling thousands of copies in the US. Unlike Warren and other African drummers such as Solomon Ilori, Olatunji's music was more 'traditional'. Using songs from his homeland and some of his own compositions (most notably Gin-Go Lo-Ba which would go on to become Jingo in the hands of Santana) Drums of Passion came off as a 'genuine' slice of Africa.

It was however, nothing of the sort. Most of the musicians on it were African Americans perhaps most notably drummers and percussionists James 'Chief' Bey (who played with Guy Warren on Themes For African Drums - read about it here), Thomas Taiwo Duvall and Montego Joe (read about his solo records here) and the singers were also from America.

Olatunji was not formerly trained as a drummer and his three co-drummers, by some accounts, provided most of the music and helped him overcome his initial limitations. Indeed in the introduction to his autobiography it is even admitted. However, Olatunji not only got top billing, the help he received remained virtually unknown.

All three percussionists appear on Zungo which was released in 1961, together with Yusef Lateef on winds, Clark Terry on trumpet, George Duvivier on bass, and Ray Barretto on conga and timbalis. Interestingly Lateef, Montego Joe and Chief Bey would go on to play on Blakey's African Beat (read about it here) in 1962, while the previous year, 1960, saw Lateef, Duvivier and Olatunji play on Randy Weston's Uhuru Africa. The 'Africa' link surely doesn't need to be pointed out!

Why was he so popular both with the jazz world and with record buyers if his playing was questionable and his music lacking in authenticity? Part of the answer lies in Lateef's recollections of playing with him. In his autobiography Lateef writes: "Later in 1960, I moved from Mingus to a group led by Babatunde Olatunji, the Nigerian percussionist. Playing with Babatunde was an interesting experience, mostly because for the first time I had to perform without a pianist or bassist in the group. It provided me with a lot of harmonic space and freedom. Olatunji's music also provided a wider appreciation for world music. To this extent he was a pioneer of what is termed today 'world music'."

For Lateef, Olatunji represented an opportunity to play with an authentic African drummer and to learn about African drumming so as to incorporate it into jazz. The same was true of John Coltrane, who became friends with Olatunji and he and Lateef agreed to help him financially with his Center of African Culture. Indeed the last concert that Coltrane played, and the last recording of him playing, was at a benefit for Olatunji's Center. Coltrane was always interested in rhythm and drummers and his love of playing with Elvin Jones because of his fierce drumming style is well documented. Coltrane also said in interviews that he intended to record with Olatunji or at least learn about 'African' drumming and music from him.

Even Nina Simone recorded Zungo, from this album, on her At the Village Gate LP. And Jack Kerouac, according to the sleeve note, loved Olatunji. Guy Warren must have been very put out by the song Jolly Mensah. After all he had actually played with the highlife king!

So, Olatunji represented a potential new musical direction but also a physcial manifestation of pride in Africa and, for African American, African culture. At a time when Africa was coming out of the oppressive period of empire and was yet to succumb to other forms of economic colonialism, the continent could become a source of pride for African Americans. Meanwhile, 1960 also saw the sit in protests in the US (shown in graphic form on the cover of Max Roach's We Insist), while 1961 and 1962 saw more sit ins, freedom rides and boycotts across the Southern states of the US.

However, despite his success both commercially and professionally I find Olatunji's music to be rather flat. It often lacks the rhythmic intricacies of other percussion records, notably by Guy Warren and Solomon Ilori. Both these musicians also strove, and sometime wonderfully succeeded to fuse Western jazz and African 'traditional' music, as well as the already existing fusion that was highlife. Lateef and Coltrane may have been fascinated by Olatunji's music, and I suspect that this was because he was perceived as authentic. They wanted something that sounded 'African' rather than sounding too 'Western'. Through wanting to create a fusion of their music with 'authentic African' music, ironically, American jazz musicians and record buyers ignored the music that already existed that was already a fusion of the two - highlife.

very thoughtful comments. i see it even today, out here in West Texas. A Guinean teacher comes thru and people eat it up, but don't really have the experience to evaluate what he's teaching them.

ReplyDelete