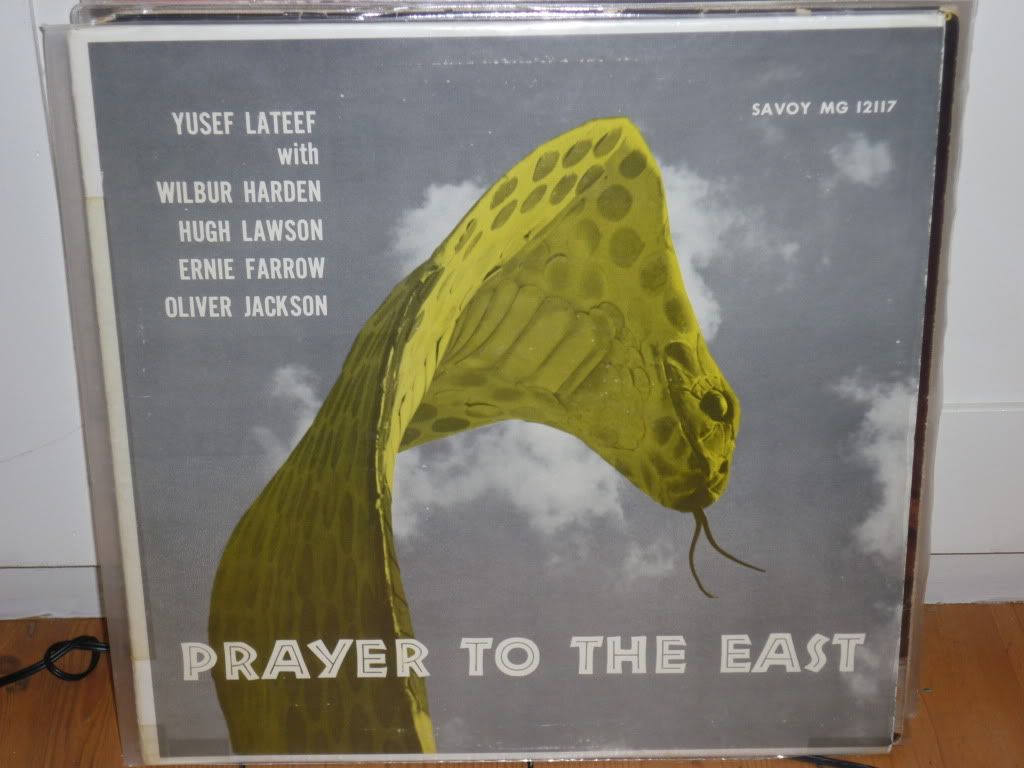

Ever since I found Eastern Sounds in a charity shop in Hammersmith I've been fascinated by Yusef Lateef - the man and his music.

He seems to me to have been unfairly relegated to a footnote in jazz history. He is mentioned as a friend of Coltrane's who made available to him books about Islam. If he is mentioned it is usually in the context of some of the exotic instruments he used such as the rahab, shanai, koto, Chinese wooden flutes as well as the oboe and the flute. Sometime he is referred to as a precursor of 'world music' - whatever that may mean. The depth and beauty of his music, however, is rarely mentioned.

Jazz musicians have always attempted to expand the range of the music through the use of different instruments, different combination of instruments and different ways of playing.

Lateef's interest in 'exotic' instruments should be seen against the background of the introduction into jazz of a range of unlikely instruments from the harp to the cello to the bagpipes. Before sounds could be generated by a computer they had to be made by people and jazz musicians were always looking for new sounds. The long shadow cast by bebop encouraged younger musicians to experiment with form as well as content. Nothing was off limits, everything could be co-opted from Broadway musicals, to classical music and even in the case of Sonny Rollins, calypso.

However, Lateef carried these experiments furthest, at least until the seventies. From the early fifties when he started to lead his own groups almost every record he made has at least one track on which he plays oboe, flute or another instrument from beyond the United States.

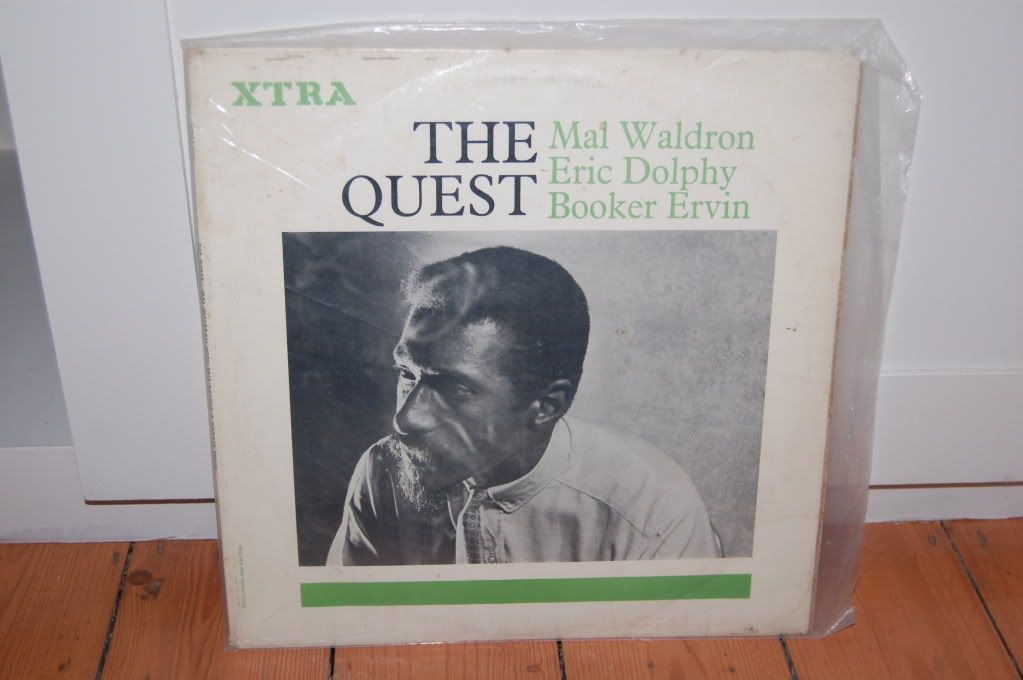

To this love of different sounds Lateef added a love of the blues. Unlike Eric Dolphy who sometime seemed to be dismantling the post bop/ hard bop sound, Lateef used his ability as a multi-instrumentalist to give the blues based form of jazz a dose of energy, to revitalise it and to make it relevant.

Lateef puts it best himself: "Having completed two albums for Savoy, it dawned on me that perhaps I could be recording for few years, and it was no use reinventing the wheel with each new album. To break the mould, I began to study other instruments from different cultures. This new pursuit meant I had to spend time in the public library doing the research on Africa, India, Japan and China."

But the use of other instrument was not just a gimmick. As well as introducing new musical sounds Lateef hoped that the use of instruments from other countries could help to promote understanding and possibly friendship. He felt that other cultures had much to teach the US and that interaction could be beneficial to all involved.

I am certain that his interest in different musical instruments and in religion, leading to his conversion to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, are linked. Indeed later in his life Lateef would travel to Nigeria to teach music but also to study Nigerian music. Lateef also became an educator and developed his theory of Autophysiopsychic music. Clearly he is a man who with a deeply searching and enquiring mind.

Lateef fully converted to Islam in 1948, after a few years of intense study. In his biography he recalls: "My embrace of Islam came in about 1946 while I was working with the Wally Hayes Band in a club on the west side of Chicago. One night a trumpet player named Talib Dawud sat-in with us. He told me that he was an itinerant musician and that he was practicing Islam as a member of the Ahmadiyya Movement."

I think that it is significant for Lateef's music that he chose the Ahmadiyya Movement rather than the, albeit still nascent Nation of Islam. The motto of the movement is 'Love for All: Hatred for None' and, although it has been rejected by heretical, particularly in Pakistan, it is far closer to the mainstream of Islam that the Nation of Islam.

Although one could infer that the adoption of Islam by Lateef, changing not only his name but the names of his wife and children, was an implicit rejection of elements of post-war American culture, Lateef does not seem to have been militantly calling for mass change. As he puts it, "I believe that the motivation for any human being to embrace Islam is that when almighty God turns a person's heart towards Islam (peace) there is no other choice for the person." This does not sound to me like the words of a many set on violent change - or indeed violence of any sort!

In a passage of Dizzy Gillespie's autobiography that is often quoted, Gillespie attributes the attraction of Islam to black Americans to the fact that they would treated with respect and as equals, something that could not easily be found in American institutions of the 1950s. Gillespie goes on to recount a story of one of his band members persuading a racist restaurateur to serve him by saying that he was not a Negro but a Muslim.

For Lateef, and indeed other jazz musicians such as Art Blakey, Dakota Stanton, Ahmad Jamal, McCoy Tyner and Shihab Sihab, conversion was a matter of deep faith not expedience

The record opens with Dizzy Gillespie's A Night In Tunisia.

The track begins with a gong and Lateef playing eastern sounding notes while in the background there are strange percussive sounds. Altogether a very evocative beginning , perhaps derived from Lateef's studies of North African musics or from folk records from the region.

The song soon, however, returns to the US and follows the well trod path of other covers of this standard. In 1957 when this record was made, Lateef

Lateef had played in Gillespie's band and must have been very familiar with Night In Tunisia. Written in 1942 and first recorded in 1944 the title refers to the Allied involvement in Tunisia rather than attempting to evoke a mythical exotic paradise.

I particularly like the very end where Lateef and trumpeter Wilbur Harden quote Charlie Parker's famous version. Harden would record four albums as leader with John Coltrane - yet another Coltrane connection!

Endura, written by Lateef is a very straightforward post bop number with fine solos from Lateef on tenor and Harden on flugelhorn. It swings in a funky manner but after Night In Tunisia is seems rather flat to my ears.

Side Two opens, like Side One, with a gong. Bassist Ali Jackson, who would also play with Coltrane as well as on other dates with Lateef, provides the wonderful Prayer to the East. Lateef's flute soars majestically above the tight rhythm section. Although the use of the flute seems to be an attempt to invoke a sense of prayer or reverence, Harden's flugelhorn is just too loud and tough to hold the same mood.

I find the next track fascinating. Why Lateef chose to cover exotica maestro Les Baxter's Love Dance, perhaps we will never know. He must have owned, or at least have had access to a copy of Baxter's Le Sacre Du Savage.

Exotica has become renowned for its fakeness, its lack of authenticity and its use of foreign instruments, usually from the Pacific, to spice up some otherwise pedestrian music. Les Baxter, however, was the one who started it all and his music is never pedestrian. The Ritual of the Savage LP contains Quiet Village which when covered by Martin Denny on his Exotica LP became a smash hit.

I think its worth quoting the description of this track on the Ritual of the Savage sleeve notes.

"The fervid sun has dropped behind the jungle curtain ... living creatures of the tropics make their nests. A chattering chimp squawls a final command to its young. Over the softening sounds of evening comes the beat of the tom-tom... bringing together the entire native populace for a ritual as stimulating as it is sacred. Here is music for a slow, surging and erotic dance ... a dance as seductive and pulsating in its concept as in its execution ... gentle in tempo ... violent in extreme." Heady stuff!!!! And I still don't understand why Lateef would have covered it.

If anything it threatens to give credence to accusations that he is just using foreign instruments in the same manner of people like Denny or Arthur Lyman - as pure exotica, employed only to evoke a feeling of a dangerous, sexually freer primitive place.

Did Lateef, still a young man of 36 really believe in the savage and primitive nature of Africa?

The sleeve states that Love Dance was arranged by Ali Mohammed Jackson, no doubt the same Ali Jackson who wrote Prayer to the East. From the name one can infer that he is a Muslim too.

The set concludes with the lovely ballad Lover Man which shows the depth of Lateef's playing to the full.

He seems to me to have been unfairly relegated to a footnote in jazz history. He is mentioned as a friend of Coltrane's who made available to him books about Islam. If he is mentioned it is usually in the context of some of the exotic instruments he used such as the rahab, shanai, koto, Chinese wooden flutes as well as the oboe and the flute. Sometime he is referred to as a precursor of 'world music' - whatever that may mean. The depth and beauty of his music, however, is rarely mentioned.

Jazz musicians have always attempted to expand the range of the music through the use of different instruments, different combination of instruments and different ways of playing.

Lateef's interest in 'exotic' instruments should be seen against the background of the introduction into jazz of a range of unlikely instruments from the harp to the cello to the bagpipes. Before sounds could be generated by a computer they had to be made by people and jazz musicians were always looking for new sounds. The long shadow cast by bebop encouraged younger musicians to experiment with form as well as content. Nothing was off limits, everything could be co-opted from Broadway musicals, to classical music and even in the case of Sonny Rollins, calypso.

However, Lateef carried these experiments furthest, at least until the seventies. From the early fifties when he started to lead his own groups almost every record he made has at least one track on which he plays oboe, flute or another instrument from beyond the United States.

To this love of different sounds Lateef added a love of the blues. Unlike Eric Dolphy who sometime seemed to be dismantling the post bop/ hard bop sound, Lateef used his ability as a multi-instrumentalist to give the blues based form of jazz a dose of energy, to revitalise it and to make it relevant.

Lateef puts it best himself: "Having completed two albums for Savoy, it dawned on me that perhaps I could be recording for few years, and it was no use reinventing the wheel with each new album. To break the mould, I began to study other instruments from different cultures. This new pursuit meant I had to spend time in the public library doing the research on Africa, India, Japan and China."

But the use of other instrument was not just a gimmick. As well as introducing new musical sounds Lateef hoped that the use of instruments from other countries could help to promote understanding and possibly friendship. He felt that other cultures had much to teach the US and that interaction could be beneficial to all involved.

I am certain that his interest in different musical instruments and in religion, leading to his conversion to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, are linked. Indeed later in his life Lateef would travel to Nigeria to teach music but also to study Nigerian music. Lateef also became an educator and developed his theory of Autophysiopsychic music. Clearly he is a man who with a deeply searching and enquiring mind.

Lateef fully converted to Islam in 1948, after a few years of intense study. In his biography he recalls: "My embrace of Islam came in about 1946 while I was working with the Wally Hayes Band in a club on the west side of Chicago. One night a trumpet player named Talib Dawud sat-in with us. He told me that he was an itinerant musician and that he was practicing Islam as a member of the Ahmadiyya Movement."

I think that it is significant for Lateef's music that he chose the Ahmadiyya Movement rather than the, albeit still nascent Nation of Islam. The motto of the movement is 'Love for All: Hatred for None' and, although it has been rejected by heretical, particularly in Pakistan, it is far closer to the mainstream of Islam that the Nation of Islam.

Although one could infer that the adoption of Islam by Lateef, changing not only his name but the names of his wife and children, was an implicit rejection of elements of post-war American culture, Lateef does not seem to have been militantly calling for mass change. As he puts it, "I believe that the motivation for any human being to embrace Islam is that when almighty God turns a person's heart towards Islam (peace) there is no other choice for the person." This does not sound to me like the words of a many set on violent change - or indeed violence of any sort!

In a passage of Dizzy Gillespie's autobiography that is often quoted, Gillespie attributes the attraction of Islam to black Americans to the fact that they would treated with respect and as equals, something that could not easily be found in American institutions of the 1950s. Gillespie goes on to recount a story of one of his band members persuading a racist restaurateur to serve him by saying that he was not a Negro but a Muslim.

For Lateef, and indeed other jazz musicians such as Art Blakey, Dakota Stanton, Ahmad Jamal, McCoy Tyner and Shihab Sihab, conversion was a matter of deep faith not expedience

The record opens with Dizzy Gillespie's A Night In Tunisia.

The track begins with a gong and Lateef playing eastern sounding notes while in the background there are strange percussive sounds. Altogether a very evocative beginning , perhaps derived from Lateef's studies of North African musics or from folk records from the region.

The song soon, however, returns to the US and follows the well trod path of other covers of this standard. In 1957 when this record was made, Lateef

Lateef had played in Gillespie's band and must have been very familiar with Night In Tunisia. Written in 1942 and first recorded in 1944 the title refers to the Allied involvement in Tunisia rather than attempting to evoke a mythical exotic paradise.

I particularly like the very end where Lateef and trumpeter Wilbur Harden quote Charlie Parker's famous version. Harden would record four albums as leader with John Coltrane - yet another Coltrane connection!

Endura, written by Lateef is a very straightforward post bop number with fine solos from Lateef on tenor and Harden on flugelhorn. It swings in a funky manner but after Night In Tunisia is seems rather flat to my ears.

Side Two opens, like Side One, with a gong. Bassist Ali Jackson, who would also play with Coltrane as well as on other dates with Lateef, provides the wonderful Prayer to the East. Lateef's flute soars majestically above the tight rhythm section. Although the use of the flute seems to be an attempt to invoke a sense of prayer or reverence, Harden's flugelhorn is just too loud and tough to hold the same mood.

I find the next track fascinating. Why Lateef chose to cover exotica maestro Les Baxter's Love Dance, perhaps we will never know. He must have owned, or at least have had access to a copy of Baxter's Le Sacre Du Savage.

Exotica has become renowned for its fakeness, its lack of authenticity and its use of foreign instruments, usually from the Pacific, to spice up some otherwise pedestrian music. Les Baxter, however, was the one who started it all and his music is never pedestrian. The Ritual of the Savage LP contains Quiet Village which when covered by Martin Denny on his Exotica LP became a smash hit.

I think its worth quoting the description of this track on the Ritual of the Savage sleeve notes.

"The fervid sun has dropped behind the jungle curtain ... living creatures of the tropics make their nests. A chattering chimp squawls a final command to its young. Over the softening sounds of evening comes the beat of the tom-tom... bringing together the entire native populace for a ritual as stimulating as it is sacred. Here is music for a slow, surging and erotic dance ... a dance as seductive and pulsating in its concept as in its execution ... gentle in tempo ... violent in extreme." Heady stuff!!!! And I still don't understand why Lateef would have covered it.

If anything it threatens to give credence to accusations that he is just using foreign instruments in the same manner of people like Denny or Arthur Lyman - as pure exotica, employed only to evoke a feeling of a dangerous, sexually freer primitive place.

Did Lateef, still a young man of 36 really believe in the savage and primitive nature of Africa?

The sleeve states that Love Dance was arranged by Ali Mohammed Jackson, no doubt the same Ali Jackson who wrote Prayer to the East. From the name one can infer that he is a Muslim too.

The set concludes with the lovely ballad Lover Man which shows the depth of Lateef's playing to the full.