It's often said that the British are a literary nation, particularly when discussing the nation's relationship to visual arts.

However, we are also a nation that likes music and in the early part of the sixties, very briefly, there seemed to be a moment when literary words and jazz might become bedfellows.

Jazz and poetry had already been having a liaison in the United States. The beats, in the main, loved jazz. Writers and poets such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac and Kenneth Rexroth recorded their poetry in jazz settings and many others praised the world of jazz in their work. The relationship between the beats and jazz was by no means straight forward and it has been pointed out that the racial tensions of 50s America were revealed in this relationship. Nevertheless one of the aspects that made jazz so appealing to the beats was that is was seen to be music from outside the (white) mainstream. It was, according to them, music that was somehow more in touch with emotions and music that was part of the popular, rather than highbrow, culture.

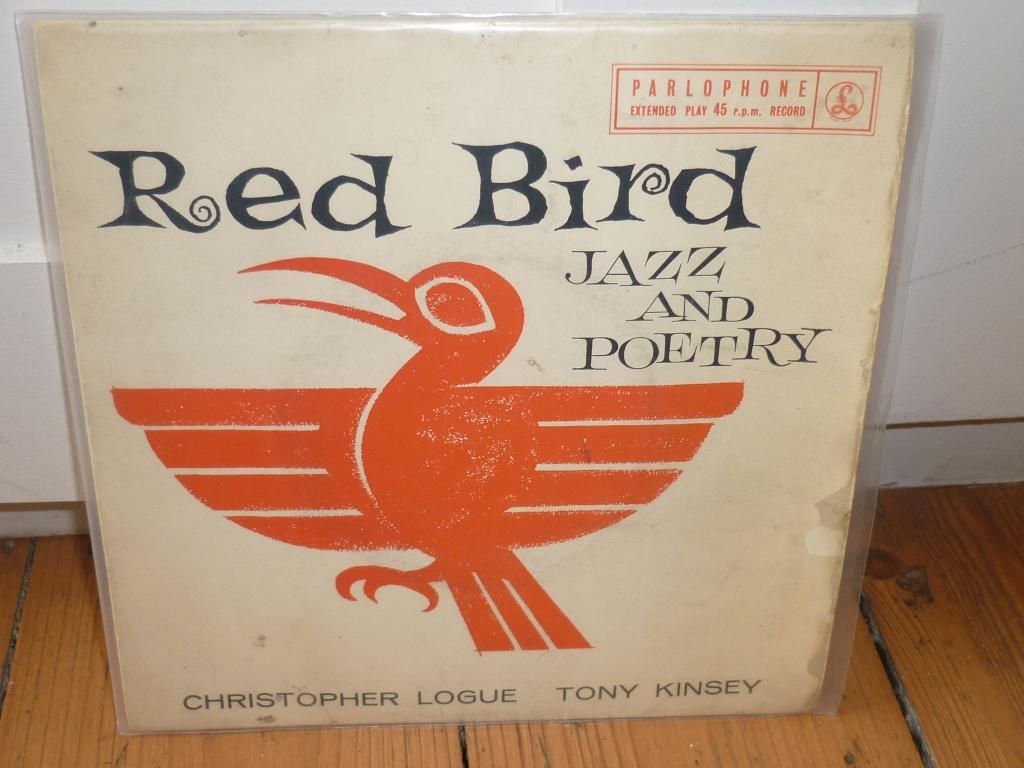

In Britain the worlds of jazz and poetry didn't make it on to vinyl until 1959 when Red Bird, Jazz and Poetry by poet Christopher Logue and drummer and band leader Tony Kinsey was released.

In some ways Logue could be seen as the link between the beats and British jazz-poetry. In the mid-1950's he lived in Paris and became friends with Scottish poet/writer and heroin addict Alexander Trocchi. Trocchi later moved to the US where he moved in beat circles.

Logue was also something of an outsider as he was a pacifist who was very involved in both anti-war and anti-nuclear arms movements. Both of these interests aligned him to many in the British jazz world.

According to the sleeve notes, the pieces on this EP were originally broadcast on the BBC.

Logue is a very intriguing poet, not least for the ways in which his political views were expressed in his work. Although he could be direct, often the politically message is implicit rather than explicit.

Logue performs his poetry while the music is played behind him by Les Condon, Kenny Wray, Bill Le Sage, Kenny Napper and Tony Kinsey - all names that will be familiar to anyone with even the slightest knowledge of British jazz. Le Sage and Kinsey composed the music around Logue poetry and it shows. Logue's voice, with it's received English pronunciation and slightly arch and melodramatic delivery, is pushed to the front of the mix, with the effect that the music is often background to the words. This split between the music and the words is alluded to on the record sleeve which lists each track as having a name for the poem and a different name for the music. Largely the poems deal with romantic problems, or rather the hypocrisies of 'modern' love.

Listen for yourself. I feel that the You tube poster dismisses Logue and the music too quickly. Although I have to admit I don't often listen to this EP, it is wrong to approach it as a comedic relic.

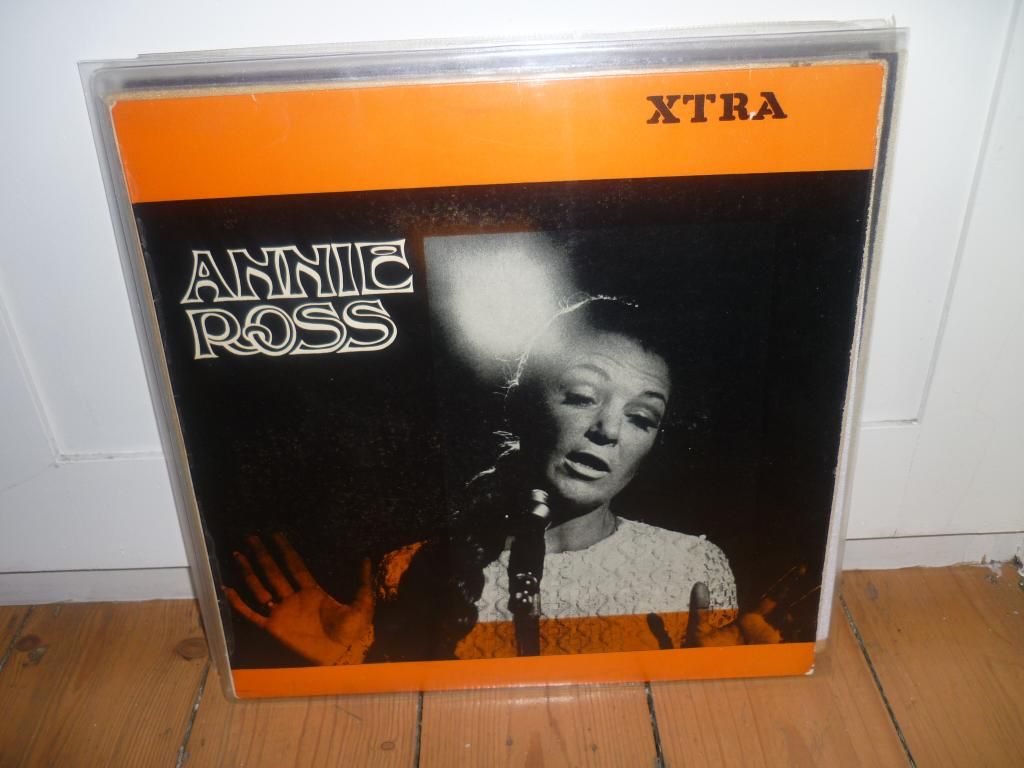

If you want to hear Logue and Jazz getting it on beautifully then you must track down Annie Ross with the Tony Kinsey Quintet.

There is another slightly earlier edition of this record called Loguerhythms from 1963 - mine is on Xtra from 1966.

Annie and Tony and the band reprise songs for the LP that they have been performing at Soho's Establishment Club, owned by Peter Cook and dedicated to the new satire boom.

Logue's anti-establishment words must have fitted in perfectly in such a setting, however, to modern ears they sound very dated. The targets of these barbed words (capitalism, conformity, class) no longer raise the ire of audiences. Either we have become inured to the inequalities of the world or they have been solved - take your pick.

Ross is one of my all time favourite jazz singers. Like Sinatra, she sings without seeming to try. Her delivery is so natural that it fits Logue's complex words very well. Although she is singing, she does so in a way that retains the spoken-word delivery of performance poetry.

Kinsey is joined by most of his cohorts from the Red Bird recording together the Peter King, Brian Brockelhurst, Gordon Beck, Roy Willocks, Malcolm Cecil, Johnny Scott and Stanley Myers.

Just as with Red Bird the words are pushed to the foreground and are clearly meant to be the most important part of the ensemble., However, with a voice as good as Ross's that is no hardship.

Logue would further successfully mix his poetry to music when Donovan set his poem Be Not Too Hard to music in the film Poor Cow in 1967 and Joen Baez went on to cover it.

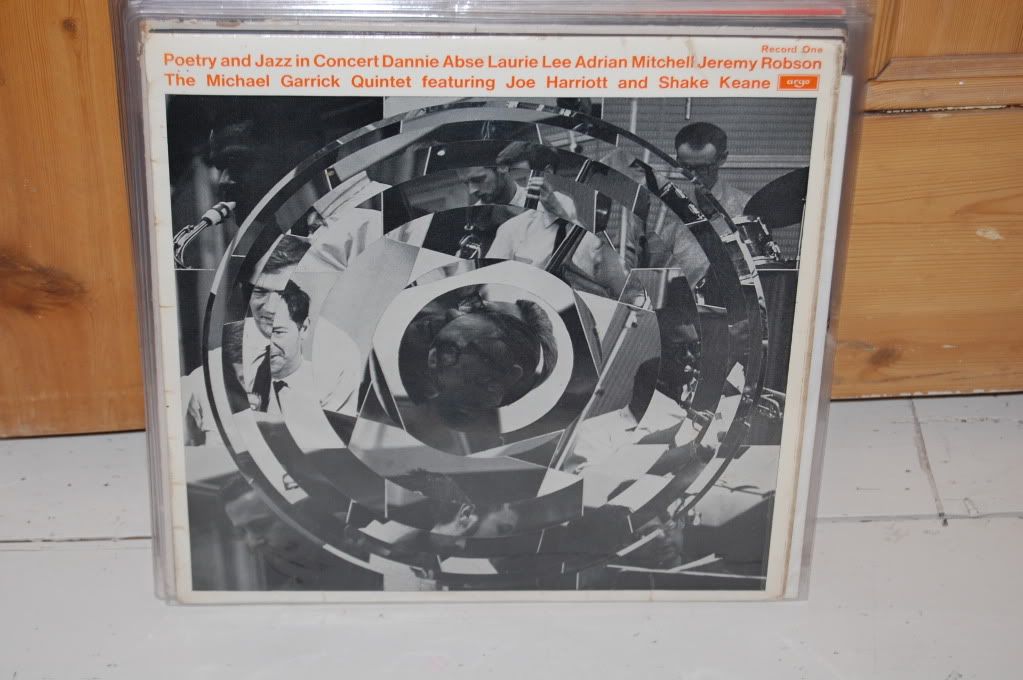

However, Logue was not the only poet that was attracted to jazz. A very different approach led to the release of Poetry and Jazz in Concert One and Two in 1964 on Argo. Argo was a fairly small but diverse record label that had released a number of recordings of poetry readings, plays, adaptations of novels and other spoken word projects, not to mention a number of recordings of steam trains.

The rational for the Poetry and Jazz was to harness some of the power (as well as the popularity) of the two art forms to their mutual benefit Intriguingly, of the musicians, Michael Garrick, Shake Keane and Joe Harriott were also deeply involved with literature. Shake Keane wrote his own poetry although he did not get much published while in England. I wonder what he though about the poets he accompanied, and about the irony of a situation of a poet playing trumpet for other poets? Did he ever want to put his trumpet down and read some of his verse? And why did no one ask him? Garrick was an English Literature student and would often use literary sources as inspiration for his music, while Harriott had been friendly with Michael Horovitz for some time. These LPs are the only recorded relics of the Poetry and Jazz movement, although there were numerous concerts and recitals throughout the mid to late 60s.

A meeting between Michael Garrick and the poet Jeremy Robson lead to a fusion of the somewhat underground jazz world and a poetry world that Robson was determined to bring above ground. Garrick brought Harriott, Keane and later Coleridge Goode on board as part of the band that would accompany the poets during their recitals. Poets such as Laurie Lee, Ted Hughes., Stevie Smith and Dannie Abse were involved at one stage or another, Not all of them were comfortable with a jazz accompaniment and on these LPs, it is only Adrian Mitchell, for his poem Pals and Jeremy Robson for his poems Approaching Mount Carmel and The Midnight Scene that have the band behind them.

The jazz is impeccable. Salvation March and Wedding Hymn on the first LP and Vishnu and She's Like Swallow are great examples of the inventiveness of mid sixties British jazz. They are all Garrick compositions but Harriott and Keane undoubtedly bring their own style. Together with Goode, they had only recently finished recording the last album in their Free Form style and in parts that iconoclastic style can be heard. Garrick was undoubtedly sympathetic to the Free Form experiment although his music is too lyrical and open to so many influences that it can never quite be subsumed into Free Form. My personal favourite is Vishnu which has some incredible solos from both Harriott and Keane as well as some amazing examples of how completely they could play as a single unit and Goode's bass solo on Wedding March is as good an example of his talent as you could wish to hear.

The poetry often touches on the same concerns as Logue's verses, class, hypocrisy, capitalism, and a counter-cultural view of the establishment. Jazz, of course, also played its part in this. Interestingly, however, by 1963 it was not a truly popular music and certainly not popular in the same was as it had been during the bid band ere in the 50s. Pop music and rock and roll were soon to be edging jazz out of people's houses. However, in 1963 jazz, and in particular the type of modern jazz played by Garrick and Harriott could be seen as an intellectual form of popular music that embodied many of the anti-establishment ideas then-current. I think it is telling that modern jazz was thought to be suitable for a concert in which the audience was seated. Long gone were the days when jazz automatically meant dancing. While you could dance to some of Garrick's music I suspect that none in the audience did.

Although Poetry and Jazz had a life that lasted well beyond these two LPs, none of it was recorded. The uneasy split between the music and the poetry, evident when you listen and clearly acknowledged by the reluctance of most of the poets to put their words to music, meant that there were no more recordings. Adrian Mitchell would go on to record with folk musician and wordsmith Leon Rosselson. I feel that, for Mitchell, this is a much more suitable setting.

While this was the end of contemporary poetry and jazz it was not quite the end of the intersection of jazz and poetry. In 1965 Stan Tracey released his Jazz Suite inspired by Under Milk Wood.

Undoubtedly one of the highlights of British Jazz, Tracey's Under Milk Wood it a beautiful record that demands repeated listening.

Tracey, together with Bobby Wellins on sax, Jeff Clyne on bass and Jack Dougan on drums take Thomas's famous long poem as a the starting point for making heart rending beautiful music.

However, I am not sure that the listener would immediately connect any of the songs on this record with Thomas. Nowhere are Thomas's words used in the music, although they do provide the names of the songs.

There is a later reissue of this record which is not expensive and I urge everyone to track down a copy and luxuriate in the beautiful music.

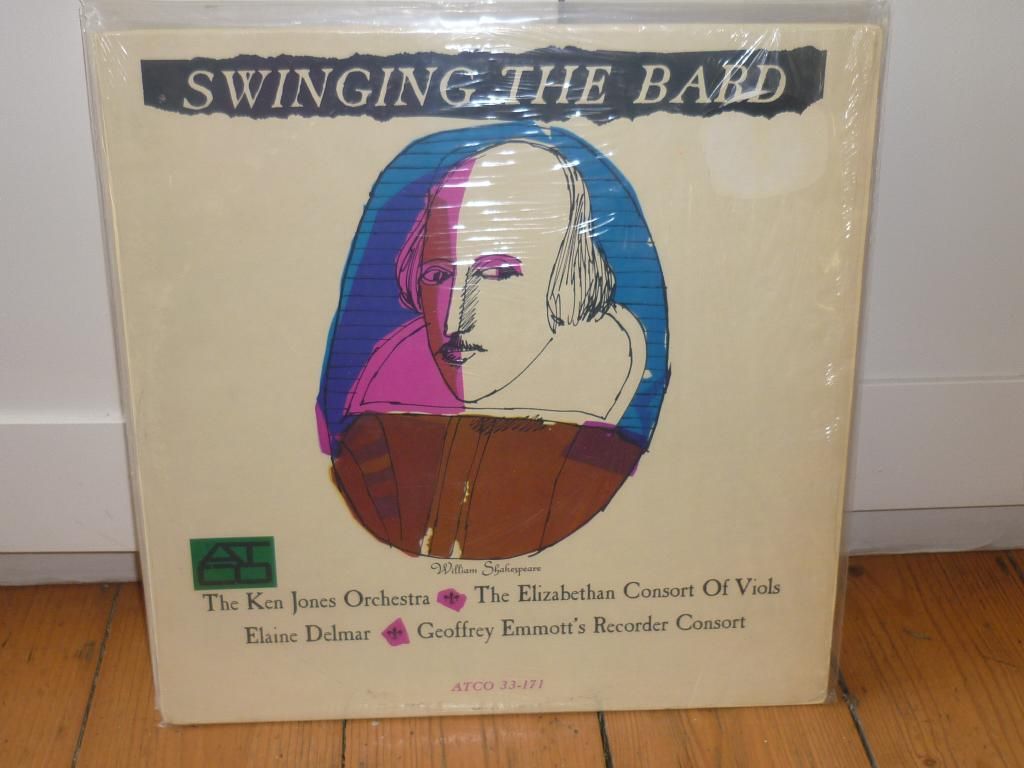

1964 was the four hundredth anniversary of the birth of William Shakespeare and to commemorate it two jazz records were released that used his verses as their basis.

The better of the two was Swinging the Bard by the Ken Jones Orchestra with Elaine Delmar. It also benefits from the inclusion of Shake Keane, Stan Tracey, Eddie Blair and Kenny Baker.

The music is provided by David Lindup, David Mack (read about his work with Shake Keane here and his work with Joe Harriott here), Ray Premu (read about him here), Johnny Hawksworth and John Mayer (read about his work with Harriott here). Phew!

Using the Elizabethan Consort of Viols and Geoffrey Emmott's Recorder Consort, together with the Bard's words this is a surprisingly effective set of songs. Unfortunately the weakest element is the married between the words and the music. Delmar is a good singer and tackles the lines with aplomb but it just doesn't swing as the title would have you believe.

David Mack's contribution is very cinematic and Keane's playing is wonderful. Meyer's piece, tablas and all, seems in some ways to be a precursor to his Indo Jazz experiments that would begin in the following year. However, his classical training, rather than his love of jazz, is all to evident here.

While there is nothing here that lifts itself above the conceit of the concept it is a great listen from start to finish. Shakespeare-ploitation anyone?

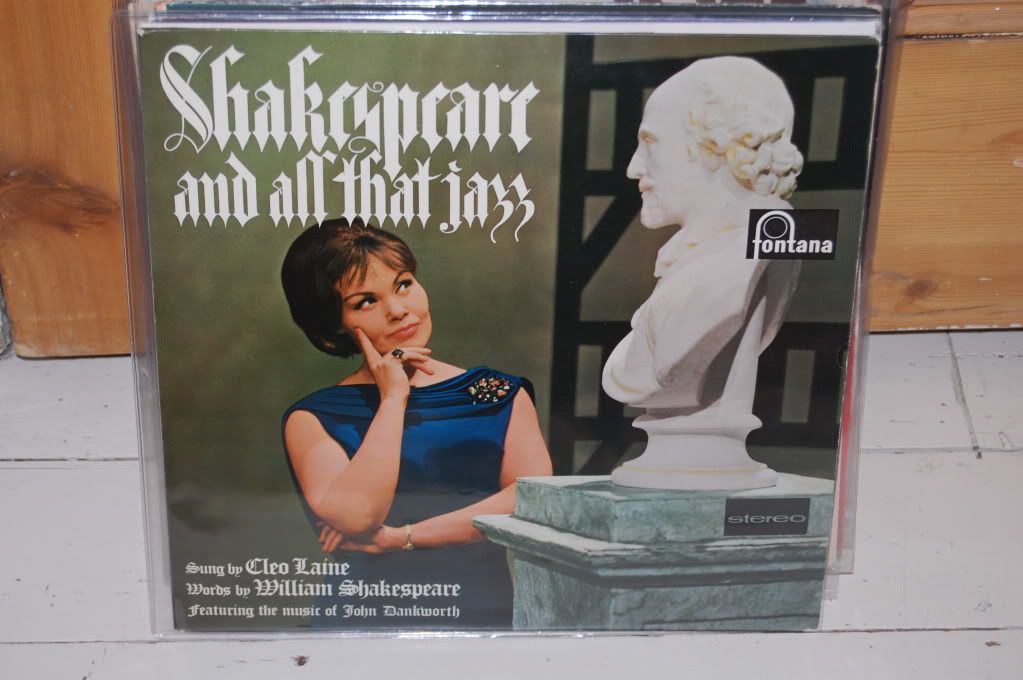

Dankworth and Cleo Laine attempt a similar exercise on their Shakespeare and All That Jazz.

Unfortunately it is not as successful as Jones's effort.

Laine's singing is good and Dankworth's music, while not breaking any boundaries is also interesting.

Unfortunately the Bard's words stubbornly refuse to translate to a jazz setting and as such the whole exercise falls flat.

However, we are also a nation that likes music and in the early part of the sixties, very briefly, there seemed to be a moment when literary words and jazz might become bedfellows.

Jazz and poetry had already been having a liaison in the United States. The beats, in the main, loved jazz. Writers and poets such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac and Kenneth Rexroth recorded their poetry in jazz settings and many others praised the world of jazz in their work. The relationship between the beats and jazz was by no means straight forward and it has been pointed out that the racial tensions of 50s America were revealed in this relationship. Nevertheless one of the aspects that made jazz so appealing to the beats was that is was seen to be music from outside the (white) mainstream. It was, according to them, music that was somehow more in touch with emotions and music that was part of the popular, rather than highbrow, culture.

In Britain the worlds of jazz and poetry didn't make it on to vinyl until 1959 when Red Bird, Jazz and Poetry by poet Christopher Logue and drummer and band leader Tony Kinsey was released.

In some ways Logue could be seen as the link between the beats and British jazz-poetry. In the mid-1950's he lived in Paris and became friends with Scottish poet/writer and heroin addict Alexander Trocchi. Trocchi later moved to the US where he moved in beat circles.

Logue was also something of an outsider as he was a pacifist who was very involved in both anti-war and anti-nuclear arms movements. Both of these interests aligned him to many in the British jazz world.

According to the sleeve notes, the pieces on this EP were originally broadcast on the BBC.

Logue is a very intriguing poet, not least for the ways in which his political views were expressed in his work. Although he could be direct, often the politically message is implicit rather than explicit.

Logue performs his poetry while the music is played behind him by Les Condon, Kenny Wray, Bill Le Sage, Kenny Napper and Tony Kinsey - all names that will be familiar to anyone with even the slightest knowledge of British jazz. Le Sage and Kinsey composed the music around Logue poetry and it shows. Logue's voice, with it's received English pronunciation and slightly arch and melodramatic delivery, is pushed to the front of the mix, with the effect that the music is often background to the words. This split between the music and the words is alluded to on the record sleeve which lists each track as having a name for the poem and a different name for the music. Largely the poems deal with romantic problems, or rather the hypocrisies of 'modern' love.

Listen for yourself. I feel that the You tube poster dismisses Logue and the music too quickly. Although I have to admit I don't often listen to this EP, it is wrong to approach it as a comedic relic.

If you want to hear Logue and Jazz getting it on beautifully then you must track down Annie Ross with the Tony Kinsey Quintet.

There is another slightly earlier edition of this record called Loguerhythms from 1963 - mine is on Xtra from 1966.

Annie and Tony and the band reprise songs for the LP that they have been performing at Soho's Establishment Club, owned by Peter Cook and dedicated to the new satire boom.

Logue's anti-establishment words must have fitted in perfectly in such a setting, however, to modern ears they sound very dated. The targets of these barbed words (capitalism, conformity, class) no longer raise the ire of audiences. Either we have become inured to the inequalities of the world or they have been solved - take your pick.

Ross is one of my all time favourite jazz singers. Like Sinatra, she sings without seeming to try. Her delivery is so natural that it fits Logue's complex words very well. Although she is singing, she does so in a way that retains the spoken-word delivery of performance poetry.

Kinsey is joined by most of his cohorts from the Red Bird recording together the Peter King, Brian Brockelhurst, Gordon Beck, Roy Willocks, Malcolm Cecil, Johnny Scott and Stanley Myers.

Just as with Red Bird the words are pushed to the foreground and are clearly meant to be the most important part of the ensemble., However, with a voice as good as Ross's that is no hardship.

Logue would further successfully mix his poetry to music when Donovan set his poem Be Not Too Hard to music in the film Poor Cow in 1967 and Joen Baez went on to cover it.

However, Logue was not the only poet that was attracted to jazz. A very different approach led to the release of Poetry and Jazz in Concert One and Two in 1964 on Argo. Argo was a fairly small but diverse record label that had released a number of recordings of poetry readings, plays, adaptations of novels and other spoken word projects, not to mention a number of recordings of steam trains.

The rational for the Poetry and Jazz was to harness some of the power (as well as the popularity) of the two art forms to their mutual benefit Intriguingly, of the musicians, Michael Garrick, Shake Keane and Joe Harriott were also deeply involved with literature. Shake Keane wrote his own poetry although he did not get much published while in England. I wonder what he though about the poets he accompanied, and about the irony of a situation of a poet playing trumpet for other poets? Did he ever want to put his trumpet down and read some of his verse? And why did no one ask him? Garrick was an English Literature student and would often use literary sources as inspiration for his music, while Harriott had been friendly with Michael Horovitz for some time. These LPs are the only recorded relics of the Poetry and Jazz movement, although there were numerous concerts and recitals throughout the mid to late 60s.

A meeting between Michael Garrick and the poet Jeremy Robson lead to a fusion of the somewhat underground jazz world and a poetry world that Robson was determined to bring above ground. Garrick brought Harriott, Keane and later Coleridge Goode on board as part of the band that would accompany the poets during their recitals. Poets such as Laurie Lee, Ted Hughes., Stevie Smith and Dannie Abse were involved at one stage or another, Not all of them were comfortable with a jazz accompaniment and on these LPs, it is only Adrian Mitchell, for his poem Pals and Jeremy Robson for his poems Approaching Mount Carmel and The Midnight Scene that have the band behind them.

The jazz is impeccable. Salvation March and Wedding Hymn on the first LP and Vishnu and She's Like Swallow are great examples of the inventiveness of mid sixties British jazz. They are all Garrick compositions but Harriott and Keane undoubtedly bring their own style. Together with Goode, they had only recently finished recording the last album in their Free Form style and in parts that iconoclastic style can be heard. Garrick was undoubtedly sympathetic to the Free Form experiment although his music is too lyrical and open to so many influences that it can never quite be subsumed into Free Form. My personal favourite is Vishnu which has some incredible solos from both Harriott and Keane as well as some amazing examples of how completely they could play as a single unit and Goode's bass solo on Wedding March is as good an example of his talent as you could wish to hear.

The poetry often touches on the same concerns as Logue's verses, class, hypocrisy, capitalism, and a counter-cultural view of the establishment. Jazz, of course, also played its part in this. Interestingly, however, by 1963 it was not a truly popular music and certainly not popular in the same was as it had been during the bid band ere in the 50s. Pop music and rock and roll were soon to be edging jazz out of people's houses. However, in 1963 jazz, and in particular the type of modern jazz played by Garrick and Harriott could be seen as an intellectual form of popular music that embodied many of the anti-establishment ideas then-current. I think it is telling that modern jazz was thought to be suitable for a concert in which the audience was seated. Long gone were the days when jazz automatically meant dancing. While you could dance to some of Garrick's music I suspect that none in the audience did.

Although Poetry and Jazz had a life that lasted well beyond these two LPs, none of it was recorded. The uneasy split between the music and the poetry, evident when you listen and clearly acknowledged by the reluctance of most of the poets to put their words to music, meant that there were no more recordings. Adrian Mitchell would go on to record with folk musician and wordsmith Leon Rosselson. I feel that, for Mitchell, this is a much more suitable setting.

While this was the end of contemporary poetry and jazz it was not quite the end of the intersection of jazz and poetry. In 1965 Stan Tracey released his Jazz Suite inspired by Under Milk Wood.

Undoubtedly one of the highlights of British Jazz, Tracey's Under Milk Wood it a beautiful record that demands repeated listening.

Tracey, together with Bobby Wellins on sax, Jeff Clyne on bass and Jack Dougan on drums take Thomas's famous long poem as a the starting point for making heart rending beautiful music.

However, I am not sure that the listener would immediately connect any of the songs on this record with Thomas. Nowhere are Thomas's words used in the music, although they do provide the names of the songs.

There is a later reissue of this record which is not expensive and I urge everyone to track down a copy and luxuriate in the beautiful music.

1964 was the four hundredth anniversary of the birth of William Shakespeare and to commemorate it two jazz records were released that used his verses as their basis.

The better of the two was Swinging the Bard by the Ken Jones Orchestra with Elaine Delmar. It also benefits from the inclusion of Shake Keane, Stan Tracey, Eddie Blair and Kenny Baker.

The music is provided by David Lindup, David Mack (read about his work with Shake Keane here and his work with Joe Harriott here), Ray Premu (read about him here), Johnny Hawksworth and John Mayer (read about his work with Harriott here). Phew!

Using the Elizabethan Consort of Viols and Geoffrey Emmott's Recorder Consort, together with the Bard's words this is a surprisingly effective set of songs. Unfortunately the weakest element is the married between the words and the music. Delmar is a good singer and tackles the lines with aplomb but it just doesn't swing as the title would have you believe.

David Mack's contribution is very cinematic and Keane's playing is wonderful. Meyer's piece, tablas and all, seems in some ways to be a precursor to his Indo Jazz experiments that would begin in the following year. However, his classical training, rather than his love of jazz, is all to evident here.

While there is nothing here that lifts itself above the conceit of the concept it is a great listen from start to finish. Shakespeare-ploitation anyone?

Dankworth and Cleo Laine attempt a similar exercise on their Shakespeare and All That Jazz.

Unfortunately it is not as successful as Jones's effort.

Laine's singing is good and Dankworth's music, while not breaking any boundaries is also interesting.

Unfortunately the Bard's words stubbornly refuse to translate to a jazz setting and as such the whole exercise falls flat.