The 1950s in South Africa saw a renaissance in music, writing, theatre and even in a small way in film. Ironically given the rise of the apartheid system at the same time, black artists of every sort found ways to express themselves, often in opposition to the white-run system.

A generation of well-educated and talented men and women were trying to improve not just their lives but the lives of their communities. It took a very brutal regime to snuff out these people and their desire for a better life.

But before that happened there was King Kong - All African Jazz Opera.

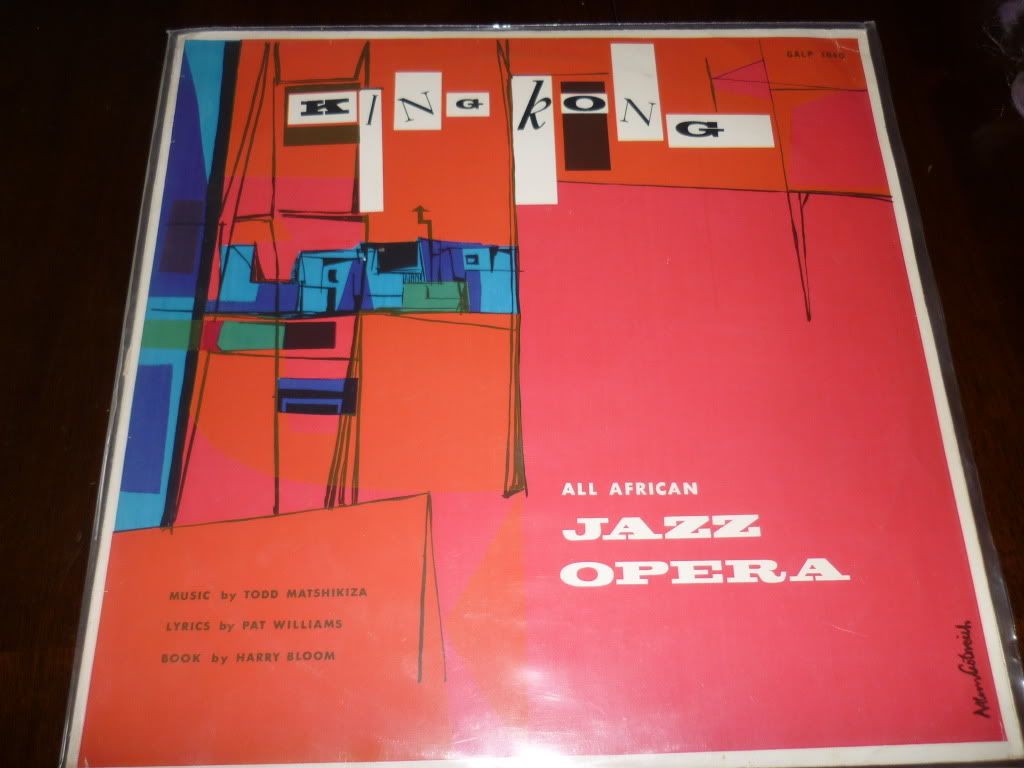

A conscious attempt to create a work that was developed by both black and white artists, King Kong became one of the most popular stage productions in South African history.

The music was written by Todd Matshikiza who, as well as being a talented musician, was also a talented writer and worked on the famous Drum magazine. He particularly liked Peter Rezant's Merry Blackbirds, a swing band in the American style, and wrote about them a number of times in Drum. He is described as using his typewriter in the same way as he played his piano.

Matshikiza had previously written choral works, apparently largely because his access to full orchestras was limited.

He was a regular at Dorkay House, a well known arts centre in central Johannesburg where musicians, writers and actors met and collaborated.

It was there that he was approached by Harry Bloom, a lawyer and writer and Percy Tucker, a booking agent, with the idea of producing a stage production using African jazz and jive.In the end the show was produced and directed by Leon Gluckman, with a script by Pat Williams, choreography by Arnold Dover and costumes by Arthur Goldreich (who also painted the picture that is on the record cover).

But it is the musicians who first attracted me to this record. The leads were taken by Nathan Mdledle (lead singer of the Manhattan Brothers) and Miriam Makeba (Mamma Africa herself).The orchestra included Gwigwi Mrwebi (who, together with some of the Blue Notes produced the Gwigwi's Kwela album in London), Mackay Davashe, Jonas Gwangwa, Kippie Moeketsi, Hugh Masakela, General Duze, Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu and finally Little Lemmy on pennywhistle. Without doubt some of the finest jazz musicians of the era.

Not only were all of the cast and musicians black South Africans but the production was resolutely about and for the new generation of urban, recently migrated black people.

The musical is set in an unnamed Township that is probably meant to represent Sophiatown. Sophiatown was to the flowering of black South African arts what Harlem was to the Harlem Renaissance. A cramped, insanitary, dangerous place with illegal drinking establishments (shebeens), armed gangs of tsotis (gangsters), unpaved roads, little street lighting or electricity or piped water. However, it was a place where music flourished, the journalists of Drum found inspiration and as one of the few places where black South Africans could own property, home to a burgeoning middle class.

It is an environment that would have resonated with all those who had migrated to Johannesburg, Cape Town or Durban and made their homes in the Townships there.

The main character is based on a real person - King Kong, the boxer Ezekiel Dhlamini. The story follows his rise and fall in the milieu of township life and ends with his arrest for the murder of his erstwhile girlfriend, the shebeen queen Joyce and his eventual suicide in prison.

It is not overtly political and therefore could be enjoyed by whites and blacks alike. However, its white liberal creators, perhaps naively thought that by showing a slice of black urban life they could persuade other whites of the humanity of their black countrymen. However, as Jonas Gwangwa points out in Gwen Ansell's Soweto Blues, it was 'well-known' that King Kong did not commit suicide in prison but was in fact killed by his jailers. Therefore, by showing that he committed suicide the musical underlined the lies of the apharteid system.

So much for the background and the relevance of the musical. What is the record like? It can surely be no coincidence that the first song on the record, Sad Times, Bad Times recalls George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue and the story has echoes of West Side Story. The music is a deliberate attempt to create a 'classical' jazz music in much the same way that Gershwin attempted while at the same time as taking themes from the white classics and weld them to indigenous approaches.

On those terms the music is a success. However, to my ears, it is a pale reflection of the jazz and jive that was being played in Sophiatown. Listen to the music on this compilation:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/South-Africa-Authentic-Selection-Township/dp/B000NTPDWI/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1296924498&sr=8-1

Now compare the joie de vivre and sheer pleasure of these tracks with King Kong. I have to say that Kong is found wanting. The exceptions are Back of the Moon where Makeba's vocals are wonderful and Kwela Kong which has some fine penny whistling.

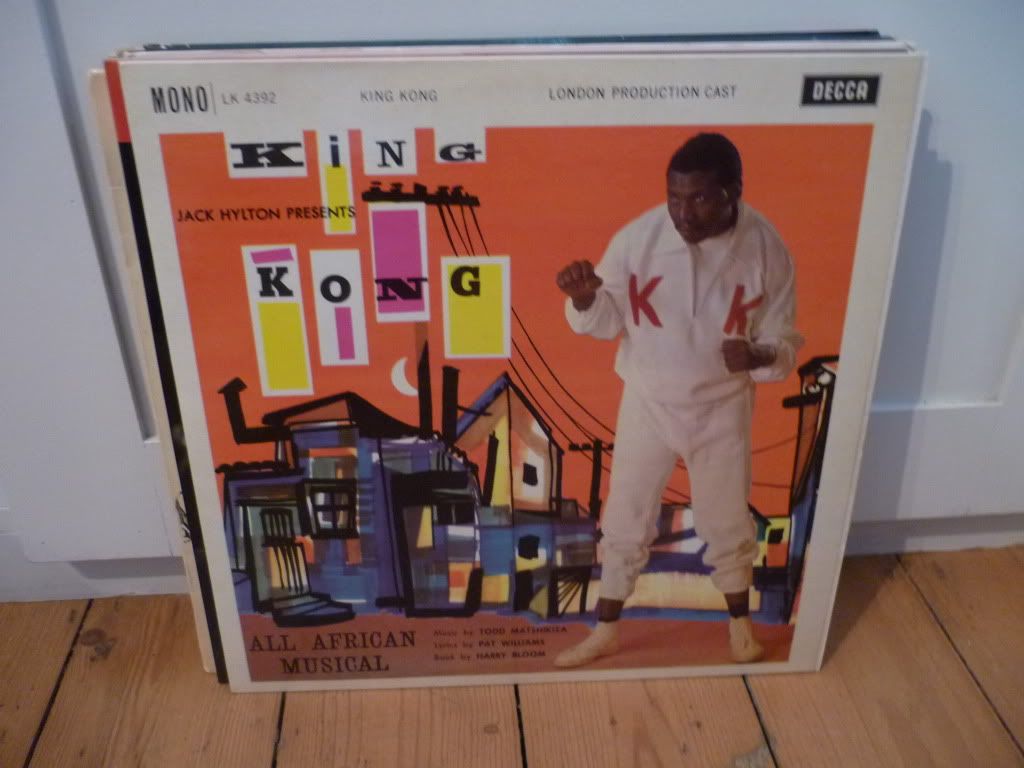

The production proved to be so popular that an opportunity to take it to London presented itself.

In 1960 most, but by no means all of the cast, went to London. Some of the musicians and actors had been denied passports on political grounds.

Many took the opportunity of being in London to flee the country, including Matshikiza.

Esme Matshikiza his wife recalled "We did it for the sake of the children, but at that point we still felt we would go home after three years or whatever. But then South Africa broke away from the Commonwealth and we had to make a choice between going back and losing job opportunities in England. There was really no choice; we decided it was best to take out British citizenship, but it was still an extremely difficult decision to make. Once we'd exchanged our citizenship we realised there was no going back, and in fact Todd never went back. By the end of his life he was a very sad man. He really wanted to go home again." Perhaps it is this fact that prompted another exile, Louis Moholo to produce such a sad cover of Wedding Song on his Spirits Rejoice album.

Strangely there are some tracks on the UK album that do not appear on the South African LP and vice versa.

The London production was slightly altered, apparently to make it more palatable to British audiences. Perhaps this made sound commercial sense. It ran for a year.

The musicians befriended some Brit jazzers, notably John Dankworth and Cleo Laine and some jammed in London's few jazz clubs, usually Ronnie Scotts. Interestingly, however, of those who did not go home, many went on the America rather than stay in Britain.

If the South African album fails to capture the elan of the jazz music of the time, the UK record is even thinner. The loss of Makeba on vocals is felt and although the 'new' tracks are very enjoyable, they are just too 'showbiz' to have any real bite.

If you are at all interested I would suggest you hunt down the South African version. Both records are important documents of their times and are interesting for containing early examples of the playing of some well known South African jazz musicians.